Revised Breast Cancer Risk w/ HRT

Also updated titles/references in other 3 articlespull/11/head

parent

dd43c1d2c0

commit

f7cb49e1e3

|

|

@ -73,7 +73,7 @@ keywords: [比卡鲁胺, 抗雄激素, 激素治疗, 安全性]

|

|||

|

||||

## 后记 {#updates}

|

||||

|

||||

### 后记一:Thompson 等人 (2021) 所作芬威健康《指南》 {#update-1}

|

||||

### 后记一:Thompson 等人 (2021) 所作芬威健康《指南》 {#update-1-thompson-et-al-2021-fenway-health-guidelines}

|

||||

|

||||

2021 年 3 月,[芬威健康][wiki54]《跨性别健康临床实践指南》自 2015 年 10 月以来首次获得更新<sup>([Aly, 2020][A20-THG])</sup>:

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -85,7 +85,7 @@ keywords: [比卡鲁胺, 抗雄激素, 激素治疗, 安全性]

|

|||

|

||||

这是第一份允许使用比卡鲁胺的《跨性别护理指南》,也是第二份纳入了比卡鲁胺的《指南》——首次纳入的是 UCSF 版《指南》,但其并不允许女性倾向跨性别者使用之。

|

||||

|

||||

### 后记二:Tomson 等人 (2021) 所作 SAHCS《指南》 {#update-2}

|

||||

### 后记二:Tomson 等人 (2021) 所作 SAHCS《指南》 {#update-2-tomson-et-al-2021-sahcs-guidelines}

|

||||

|

||||

2021 年 9 月,[南非洲艾滋病医师协会][SAHIV](SAHCS)首次发表了针对跨性别护理的《临床指南》:

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -93,7 +93,7 @@ keywords: [比卡鲁胺, 抗雄激素, 激素治疗, 安全性]

|

|||

|

||||

令人惊异的是,该《指南》不仅纳入了比卡鲁胺,而且其推荐作为抗雄制剂的程度更甚于螺内酯与醋酸环丙孕酮。对于原因,其写道:“损耗神经甾体的风险更低,因其并不易穿过血脑屏障”。不过,此效应并非除 [5α-还原酶抑制剂][wiki55]以外的抗雄制剂所引起的已知顾虑之一;而事实上,比卡鲁胺的确能够渗透到人体的神经中枢<sup>([维基百科][wiki56-d])</sup>。此外,该《指南》并未提及和比卡鲁胺相关的肝毒性或肝转化酶监测,这同样令人诧异。考虑到以上明显疏忽及其它因素,应当谨慎对待其推荐的理由。

|

||||

|

||||

### 后记三:Coleman 等人 (2022) 所作 WPATH SOC8《指南》 {#update-3}

|

||||

### 后记三:Coleman 等人 (2022) 所作 WPATH SOC8《指南》 {#update-3-coleman-et-al-2022-wpath-soc8-guidelines}

|

||||

|

||||

2022 年 9 月,[世界跨性别人士健康专业协会][wpath](WPATH)发布了第八版《[跨性别及性别多元化人群健康护理标准][soc8]》(SOC8)<sup>([Coleman et al., 2022][C22])</sup>。该《标准》是现有最权威的跨性别护理指南之一,由健康护理专家担任顾问。此指南在以下两个片段中简要讨论了比卡鲁胺:

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -104,7 +104,7 @@ keywords: [比卡鲁胺, 抗雄激素, 激素治疗, 安全性]

|

|||

|

||||

如上文所述,由于缺乏相关研究、且有潜在风险,《标准》并未建议将比卡鲁胺用于女性倾向跨性别者的常规治疗。本文也已提到,在比卡鲁胺得到主流《跨性别护理指南》的认可之前,可能还需要更多研究探索其用于女性倾向跨性别者的情况。

|

||||

|

||||

### 后记四:Jamie Reed 报告的因比卡鲁胺引起肝毒性的病例 {#update-4}

|

||||

### 后记四:Jamie Reed 报告的因比卡鲁胺引起肝毒性的病例 {#update-4-jamie-reed-bicalutamide-liver-toxicity-case}

|

||||

|

||||

2022 年二月,曾在美国密苏里州[圣路易斯儿童医院][wiki57]的[华盛顿大学跨性别中心][WUTC]担任个案经理的 Jamie Reed,在保守派网络媒体《[自由报][wiki58]》上发表了一篇专栏文章《[我曾认为我在拯救跨性别儿童,但现在我要告发][R23]》。Reed 写道,她对青年跨性别者的医疗服务大失所望,并为此表达不满。不过,她简略提到一起传闻在该中心发生的、因比卡鲁胺引起肝毒性的女性倾向跨性别者病例。据称该病例年龄为 15 岁,接受该中心的联合创始人之一:[Christopher Lewis][WUSTL-profile] 博士开出的比卡鲁胺(作为青春期阻断剂)治疗;其随后出现肝毒性,停用了比卡鲁胺。其母亲在联系该中心时说:“你们该庆幸,我们不是那种讼棍。”此案例连同 Reed 的专栏文章,在福克斯新闻、《每日邮报》等保守派媒体当中被广泛传播<sup>([Google 搜索][google-search])</sup>。\

|

||||

除了这篇专栏文章,Reed 还向密苏里州的共和党检察长 [Andrew Bailey][wiki59] 递交了一份经宣誓的证词,此后该检察长发起了对这家诊所的调查<sup>([密苏里州政府, 2023][MG23])</sup>。该证词的部分内容如下:

|

||||

|

|

@ -167,7 +167,7 @@ keywords: [比卡鲁胺, 抗雄激素, 激素治疗, 安全性]

|

|||

- Moreno-Pérez, Ó., De Antonio, I. E., & Grupo de Identidad y Diferenciación Sexual de la SEEN (GIDSEEN. (2012). Clinical practice guidelines for assessment and treatment of transsexualism. SEEN Identity and Sexual Differentiation Group (GIDSEEN). *Endocrinología y Nutrición (English Edition)*, *59*(6), 367–382. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.endoen.2012.07.004][MP12]]

|

||||

- Moretti, C. G., Guccione, L., Di Giacinto, P., Cannuccia, A., Meleca, C., Lanzolla, G., Andreadi, A., & Lauro, D. (2016). Efficacy and Safety of Myo-Inositol Supplementation in the Treatment of Obese Hirsute PCOS Women: Comparative Evaluation with OCP+Bicalutamide Therapy. *Endocrine Reviews*, *37*(2 Suppl 1) (SUN-153). \[[URL][M16]] \[DOI:[10.1093/edrv/37.supp.1][M16-DOI]]

|

||||

- Moretti, C., Guccione, L., Di Giacinto, P., Simonelli, I., Exacoustos, C., Toscano, V., Motta, C., De Leo, V., Petraglia, F., & Lenzi, A. (2018). Combined oral contraception and bicalutamide in polycystic ovary syndrome and severe hirsutism: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. *The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism*, *103*(3), 824–838. \[DOI:[10.1210/jc.2017-01186][M18]]

|

||||

- Moussa, A., Kazmi, A., Bokhari, L., & Sinclair, R. D. (2021). Bicalutamide improves minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis in female pattern hair loss: A retrospective review of 35 patients. *Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology*, online ahead of print. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.048][M21]]

|

||||

- Moussa, A., Kazmi, A., Bokhari, L., & Sinclair, R. D. (2022). Bicalutamide improves minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis in female pattern hair loss: A retrospective review of 35 patients. *Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology*, *87*(2), 488-490. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.048][M21]]

|

||||

- Muderris, I. I., Bayram, F., & Guven, M. (1999). Bicalutamide 25 mg/day in the treatment of hirsutism. *Human Reproduction*, *14*(Suppl 3), 366–366 (R-196). \[DOI:[10.1093/humrep/14.Suppl\_3.366-a][MBG99]]

|

||||

- Müderris, I. I., Bayram, F., Özçelik, B., & Güven, M. (2002). New alternative treatment in hirsutism: bicalutamide 25 mg/day. *Gynecological Endocrinology*, *16*(1), 63–66. \[DOI:[10.1080/gye.16.1.63.66][M02]]

|

||||

- Müderris, İ. İ., & Öner, G. (2009). Hirsutizm Tedavisinde Flutamid ve Bikalutamid Kullanımı. \[Flutamide and Bicalutamide Treatment in Hirsutism.] *Türkiye Klinikleri Endokrinoloji-Özel Dergisi*, *2*(2), 110–112. \[ISSN:[1308-0954][MO09-ISSN]] \[[URL][MO09]] \[[PDF][MO09-PDF]] \[[英译本][MO09-ENG]]

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

@ -4,142 +4,148 @@ linkTitle: 女性化激素疗法与乳腺癌风险

|

|||

description: 长期使用雌激素与孕激素会极大提高患乳腺癌的风险。此外 X 染色体也可显著影响乳腺癌风险。

|

||||

author: Aly

|

||||

published: 2020-04-25

|

||||

updated: 2022-11-26

|

||||

translated: 2022-11-28

|

||||

updated: 2023-03-02

|

||||

translated: 2023-03-29

|

||||

translators:

|

||||

- Bersella AI

|

||||

tags:

|

||||

- 用药安全

|

||||

- 雌激素

|

||||

- 孕激素

|

||||

trackHash: fdd701930bcb4e0f6f2c2ca8df31b80ae016e9a0

|

||||

keywords: [MtF, 激素治疗, HRT, 雌激素, 乳腺癌]

|

||||

trackHash: 802de46c25d83106f6b875fc02d91ff2d69202bf

|

||||

keywords: [激素治疗, 雌激素, 乳腺癌, 安全性]

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

## 译者按 {#notice}

|

||||

|

||||

1. 一些机构名称的链接,从维基百科的介绍页改为其官方网站。其余链接未作变动。

|

||||

1. 因译者能力所限,部分术语之翻译或有纰漏,烦请指正。

|

||||

1. 如需进一步了解乳腺癌,可参考以下视频:<https://youtu.be/I5wnbZsZ1so>

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

## 摘要 {#abstract--tldr}

|

||||

|

||||

> 雌激素与孕激素可促进乳房发育,也会引起乳腺癌风险增长。无论女性还是男性,乳腺癌风险均随年龄呈指数级增长,而女性风险的增幅远超男性。在多种情形下,雌激素和孕激素均与乳腺癌风险有关;例如卵巢活动、更年期激素疗法、抗雌激素疗法、高剂量雌激素疗法,等等。\

|

||||

> 迄今有关雌激素、孕激素对女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险之影响的研究屈指可数。尽管现有资料有限、且研究方法有局限性,但有明确证据表明雌激素与孕激素疗法可引起女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险大幅增长,风险率介乎顺性别妇女和顺性别男性。尚需更多研究来更好地确立女性倾向跨性别者的激素治疗与乳腺癌风险之间的关系;尤其是跟踪时间更长、激素处方不同(例如对比雌激素单方和雌、孕激素复方)的研究。\

|

||||

> 影响女性倾向跨性别者乳腺癌风险的可能因素有:激素治疗时长,开始激素治疗的年龄,是否长期并用孕激素,雌、孕激素剂量,等等。相比于有两条 X 染色体的顺性别妇女,顺性别男性及女性倾向跨性别者仅有一条 X 染色体,这可能有助于预防乳腺癌。\

|

||||

> 对于女性倾向跨性别者,尽管乳腺癌的风险会增长,但其终生发生率并不会高;其风险需持续多年的激素暴露以累积;其通常发生于老年;而且治疗乳腺癌也相当容易。因此,对乳腺癌风险的担忧不足以妨碍到女性倾向跨性别者的激素治疗。无论如何,应建议女性倾向跨性别者像顺性别妇女那样,接受乳腺癌筛查。

|

||||

|

||||

## 前言 {#introduction}

|

||||

|

||||

雌激素与孕激素可促进人类乳房发育。其中,雌激素在青春期乳房发育当中居主导作用;而孕激素在怀孕期间为准备泌乳和母乳喂养而产生的乳房变化当中居主导作用。较之于顺性别男性,乳腺癌在顺性别妇女当中尤其更为常见;激素被广泛认为是引起顺性别妇女的乳腺癌并发展的因素所在。据此可以合理推断:女性倾向跨性别者的激素疗法或可增加乳腺癌发病风险。本文就此观点以及既有相关研究项目进行论述。

|

||||

雌激素与孕激素可促进人类[乳房发育][wiki1]。其中,雌激素在青春期乳房发育当中居主导作用;而孕激素在怀孕期间为准备泌乳和母乳喂养而产生的乳房变化当中居主导作用。较之于顺性别男性,[乳腺癌][wiki2]在顺性别妇女当中尤其更为常见;激素被广泛认为是引起顺性别妇女的乳腺癌并发展的因素所在。据此可以合理推断:女性倾向跨性别者的激素疗法或可增加乳腺癌发病风险。本文就此观点以及既有相关研究项目进行论述。

|

||||

|

||||

## 乳腺癌风险相关因素:性别与年龄 {#sex-and-age-as-breast-cancer-risk-factors}

|

||||

|

||||

对妇女而言,其患乳腺癌的终生概率通常约为 12.5%(即每 8 人有一人罹患)<sup>([Ban & Godellas, 2014][bg14])</sup>;而男性患病概率通常约为 0.1%(即每 1000 人有一人罹患)<sup>([Yousef, 2017][y17])</sup>。男性乳腺癌的综合年化发病率约为每 100,000 人/年一例<sup>(Yousef, 2017; [Ottini & Capalbo, 2017][oc17])</sup>。在所有乳腺癌病例当中,男性占比不足 1%<sup>(Yousef, 2017; [Sun et al., 2017][s17])</sup>。综上,乳腺癌在妇女当中较常见,但在男性当中极为罕见。

|

||||

对妇女而言,其患乳腺癌的终生概率通常约为 12.5%(即每 8 人有一人罹患)<sup>([Ban & Godellas, 2014][BG14])</sup>;而男性患病概率通常约为 0.1%(即每 1000 人有一人罹患)<sup>([Abdelwahab Yousef, 2017][AY17])</sup>。男性乳腺癌的综合年化发病率约为每 100,000 人/年一例<sup>([Abdelwahab Yousef, 2017][AY17]; [Ottini & Capalbo, 2017][OC17])</sup>。在所有乳腺癌病例当中,男性占比不足 1%<sup>([Abdelwahab Yousef, 2017][AY17]; [Sun et al., 2017][S17])</sup>。综上,乳腺癌在妇女当中较常见,但在男性当中极为罕见。

|

||||

|

||||

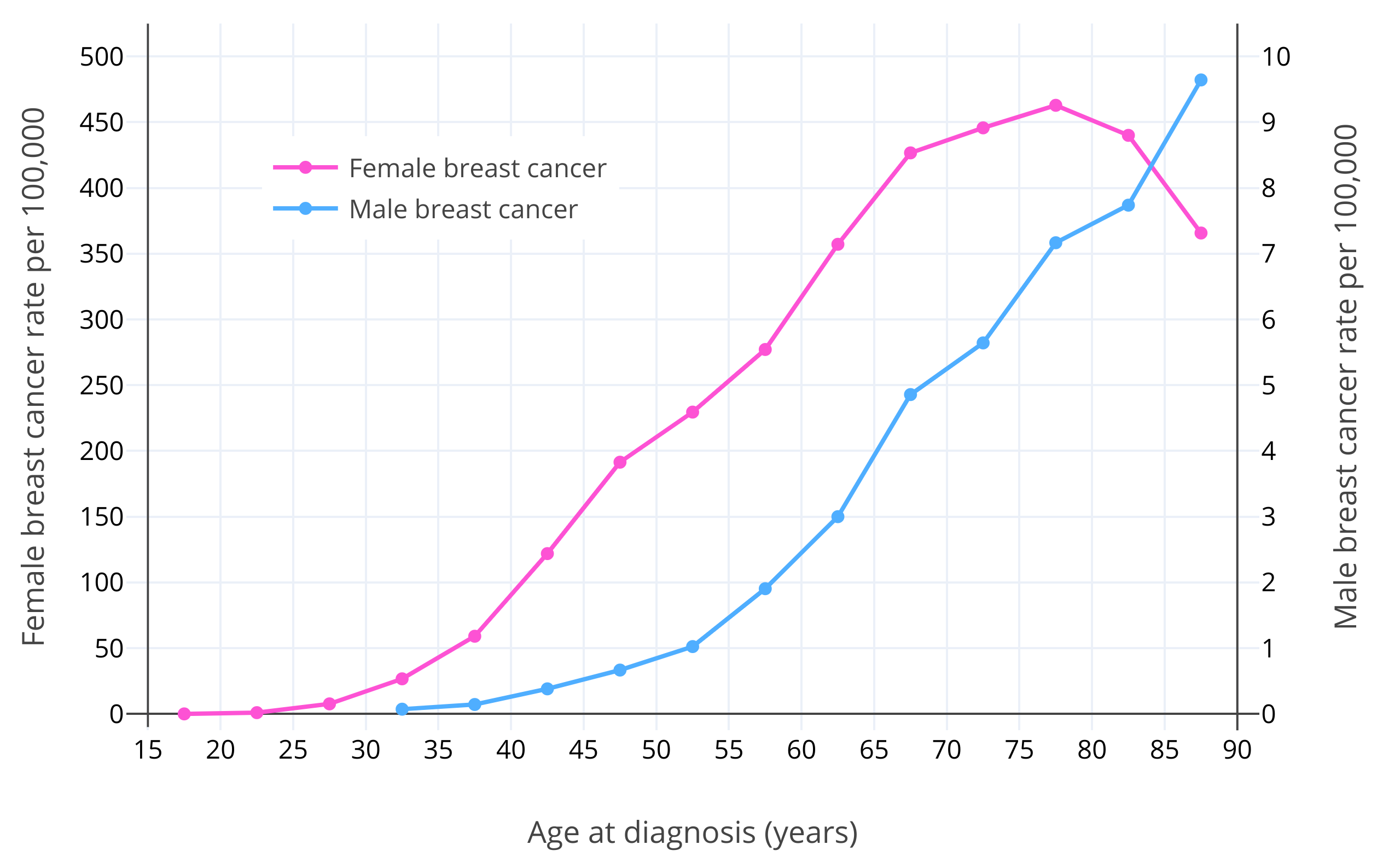

除性别之外,年龄是乳腺癌的已知最大风险因素所在<sup>([Momenimovahed & Salehiniya, 2018][ms18])</sup>。对于绝经前妇女,乳腺癌风险随年龄增长呈指数级上升之势<sup>([Dix & Cohen, 1982][dc82])</sup>。女性乳腺癌风险在 15 岁时约为 1/600,000;在 20 岁时约为 1/75,000;在 30 岁时约为 1/1,500;到了 40 岁则约为 1/175<sup>([Anders et al, 2009][a09])</sup>。在其绝经后(通常在 50 岁),乳腺癌风险仍继续增长,但增幅有所放缓<sup>(Dix & Cohen, 1982; [Benz, 2008][b08]; [Colditz & Rosner, 2000][cr00])</sup>。其原因被认为在于,雌二醇与孕激素水平在绝经后大幅减少<sup>(Dix & Cohen, 1982)</sup>。据估算,如果不曾绝经,女性乳腺癌病例会多出六倍,也即大部分女性终其一生皆会罹患乳腺癌<sup>([Brisken, Hess, & Jeitziner, 2015][bhj15])</sup>。男性的情况与女性类似,其乳腺癌发病率在大约 65 岁之前呈指数级上升之势,此后变为缓慢上升<sup>(Ottini & Capalbo, 2017; [Cancer Research UK][cruk])</sup>。这可能和男性更年期及其导致的更低的睾酮与雌二醇水平有关<sup>([Satram, 2006][s06])</sup>。女性的乳腺癌确诊年龄通常在 60 岁左右,而男性通常在 65-70 岁<sup>([Ferzoco & Ruddy, 2016][fr16]; [Giordano, 2018][g18])</sup>。下图展示了女性及男性在不同年龄的乳腺癌发病风险<sup>(Ottini & Capalbo, 2017)</sup>。

|

||||

除性别之外,年龄是乳腺癌的已知最大风险因素所在<sup>([Momenimovahed & Salehiniya, 2018][MS18])</sup>。对于绝经前妇女,乳腺癌风险随年龄增长呈指数级上升之势<sup>([Dix & Cohen, 1982][DC82])</sup>。女性乳腺癌风险在 15 岁时约为 1/600,000;在 20 岁时约为 1/75,000;在 30 岁时约为 1/1,500;到了 40 岁则约为 1/175<sup>([Anders et al., 2009][A09])</sup>。在其[绝经后][wiki3](通常在 50 岁),乳腺癌风险仍继续增长,但增幅有所放缓<sup>([Dix & Cohen, 1982][DC82]; [Benz, 2008][B08]; [Colditz & Rosner, 2000][CR00])</sup>。其原因被认为在于,雌二醇与孕酮水平在[绝经后][wiki3-p]大幅减少<sup>([Dix & Cohen, 1982][DC82])</sup>。据估算,如果不曾绝经,女性乳腺癌病例会多出六倍,也即大部分女性终其一生皆会罹患乳腺癌<sup>([Brisken, Hess, & Jeitziner, 2015][BHJ15])</sup>。男性的情况与女性类似,其乳腺癌发病率在大约 65 岁之前呈指数级上升之势,此后变为缓慢上升<sup>([Ottini & Capalbo, 2017][OC17]; [Cancer Research UK][CRUK20])</sup>。这可能和[男性更年期][wiki4]及其导致的更低的睾酮与雌二醇水平有关<sup>([Satram, 2006][S06])</sup>。女性的乳腺癌确诊年龄通常在 60 岁左右,而男性通常在 65-70 岁<sup>([Ferzoco & Ruddy, 2016][FR16]; [Giordano, 2018][G18])</sup>。下图展示了女性及男性在不同年龄的乳腺癌发病风险<sup>([Ottini & Capalbo, 2017][OC17])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

<section class="box">

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

**图 1**:在不同年龄,男性、女性美国白人每十万人当中的乳腺癌发生率。数据源自美国国家癌症研究所(NCI)的统合监测、流行病学和最终结果项目(SEER,2003-2012 年)<sup>(Ottini & Capalbo, 2017)</sup>。需要注意,男、女性所对应的 Y 坐标轴及刻度不同;女性的 Y 坐标轴(左)刻度为男性的 50 倍。

|

||||

**图 1**:在不同年龄,男性、女性美国白人每十万人当中的乳腺癌发生率。数据源自[美国国家癌症研究所][wiki6](NCI)的[统合监测、流行病学和最终结果项目][wiki5](SEER,2003-2012 年)<sup>([Ottini & Capalbo, 2017][OC17])</sup>。需要注意,男、女性所对应的 Y 坐标轴及刻度不同;女性的 Y 坐标轴(左)刻度为男性的 50 倍。

|

||||

|

||||

</section>

|

||||

|

||||

## 女性的激素暴露量与乳腺癌风险的关系 {#hormone-exposure-in-women-and-breast-cancer-risk}

|

||||

|

||||

除性别与年龄之外,有研究还强调了卵巢活动及其分泌的激素(如雌二醇与孕激素)是引起乳腺癌的主要风险因素<sup>([Ban & Godellas, 2014][bg14])</sup>。更晚的初潮、更早的更年期、以及母乳喂养,皆可让乳腺癌风险变得更低,因为上述现象可导致经卵巢分泌的激素总和暴露量更少<sup>(Ban & Godellas, 2014; Momenimovahed & Salehiniya, 2018)</sup>。如果在 40 岁以前摘除卵巢,可将乳腺癌的终生发病风险降低 50%<sup>(Ban & Godellas, 2014)</sup>。\

|

||||

对于高患癌风险的已绝经妇女,可长期预防性服用选择性雌激素受体调节剂(SERMs,如三苯氧胺)、芳香化酶抑制剂(AIs,如阿那曲唑)等抗雌激素制剂,以预防乳腺癌;其可降低 50-70% 发病风险<sup>([Mocellin, Goodwin, & Pasquali, 2019][mgp19]; [Nelson et al., 2019][n19])</sup>。\

|

||||

在灵长类动物当中,长期使用雌激素与孕激素疗法被发现可引起乳腺癌,而高剂量则让发病年龄较常规更早<sup>([Cline, 2007][c07])</sup>。

|

||||

除性别与年龄之外,有研究还强调了卵巢活动及其分泌的激素(如雌二醇与孕酮)是引起乳腺癌的主要风险因素<sup>([Ban & Godellas, 2014][BG14])</sup>。更晚的[初潮][wiki7]、更早的更年期、以及母乳喂养,皆可让乳腺癌风险变得更低,因为上述现象可导致经卵巢分泌的激素总和暴露量更少<sup>([Ban & Godellas, 2014][BG14]; [Momenimovahed & Salehiniya, 2018][MS18])</sup>。如果在 40 岁以前摘除卵巢,可将乳腺癌的终生发病风险降低 50%<sup>([Ban & Godellas, 2014][BG14])</sup>。\

|

||||

对于高患癌风险的已绝经妇女,可长期[预防性][wiki13]服用[选择性雌激素受体调节剂][wiki9](SERM,如[他莫昔芬][wiki10])、[芳香化酶抑制剂][wiki11](AI,如[阿那曲唑][wiki12])等[抗雌激素制剂][wiki8],以预防乳腺癌;其可降低 50-70% 发病风险<sup>([Mocellin, Goodwin, & Pasquali, 2019][MGP19]; [Nelson et al., 2019][N19])</sup>。\

|

||||

在灵长类动物当中,长期使用雌激素与孕激素疗法被发现可引起乳腺癌,而高剂量则让发病年龄较常规更早<sup>([Cline, 2007][C07])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

除增加乳腺癌发病风险之外,卵巢分泌的性激素还会促进活跃的乳腺癌之发展。抗雌激素制剂可有效治疗活跃当中的乳腺癌<sup>([Lumachi, Santeufemia, & Basso, 2015][lsb15])</sup>;而抗孕激素制剂(如奥那司酮、米非司酮等)亦可在乳腺癌的治疗当中取得初步成效<sup>([Palmieri et al., 2014][p14])</sup>。如患有乳腺癌的妇女服用生理剂量的雌激素,后者可加速肿瘤的发展<sup>([Herrmann, Adair, & Woodard, 1947][haw47]; [Nathanson, 1947][n47]; [Gellhorn & Jones, 1949][gj49]; [Nathanson, 1951][n51]; [Pearson et al., 1954][p54]; [Pearson & Lipsett, 1956][pl56]; [Kennedy, 1956][k56]; [Kennedy, 1957][k57]; [Dworin, 1961][d61]; [Kennedy, 1962][k62]; [Green, Sethi, & Lindner, 1964][gsl64]; [Kennedy, 1964][k64]; [Stoll, 1973][s73]; [Forrest, 1989][f89])</sup>。

|

||||

除增加乳腺癌发病风险之外,卵巢分泌的性激素还会促进活跃的乳腺癌之发展。抗雌激素制剂可有效治疗活跃当中的乳腺癌<sup>([Lumachi, Santeufemia, & Basso, 2015][LSB15])</sup>;而[抗孕激素制剂][wiki14](如[奥那司酮][wiki15]、[米非司酮][wiki16]等)亦可在乳腺癌的治疗当中取得初步成效<sup>([Palmieri et al., 2014][P14])</sup>。如患有乳腺癌的妇女服用生理剂量的雌激素,后者可加速肿瘤的发展<sup>([Herrmann, Adair, & Woodard, 1947][HAW47]; [Nathanson, 1947][N47]; [Gellhorn & Jones, 1949][GJ49]; [Nathanson, 1951][N51]; [Pearson et al., 1954][P54]; [Pearson & Lipsett, 1956][PL56]; [Kennedy, 1956][K56]; [Kennedy, 1957][K57]; [Dworin, 1961][D61]; [Kennedy, 1962][K62]; [Green, Sethi, & Lindner, 1964][GSL64]; [Kennedy, 1964][K64]; [Stoll, 1973][S73]; [Forrest, 1989][F89])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

和公认的卵巢活动与乳腺癌风险之间关系相关联的是,更年期激素疗法亦可增加更年期、已绝经妇女的乳腺癌发病风险<sup>([乳腺癌激素相关因素合作研究小组(CGHFBC), 2019][cghf19]; [图表][cghf19-table])</sup>。单服雌激素、或者合用雌激素与孕激素,皆会增加该风险,而后者增加的幅度更大<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019)</sup>。依据近期一项针对所有已有数据的大型荟萃分析,在更年期激素疗法引起的乳腺癌绝对风险上,单服雌激素达 20 年后,发病率将提高约 1.5 倍,而合用雌、孕可提高约 2.5 倍<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019)</sup>。因此,合用雌、孕疗法的乳腺癌发病风险高于单服雌激素疗法。在此之前,孕激素因其在乳房中对雌激素的拮抗效应,被认为可能对乳腺癌起抑制作用<sup>([Mauvais-Jarvis, Kuttenn, & Gompel, 1986][mkg86]; [Wren & Eden, 1996][we96]; [Gompel et al., 2002][g02])</sup>;但上述荟萃分析推翻了该假设。\

|

||||

美国[“妇女健康倡议”][whi](WHI)项目似乎也和这种由更年期激素疗法引起的高乳腺癌风险有关系,至少在一项已使用的处方上(即 0.625mg/天的结合雌激素合并 2.5 mg/天的醋酸甲羟孕酮方案);使用该疗法 5 年后,发病风险增加 1.25 倍<sup>([WHI 调查员编辑组, WGWHII, 2002][whi02]; [Chlebowski, Aragaki, & Anderson, 2015][caa15])</sup>。WHI 是迄今规模最大的激素疗法随机对照试验项目,其为评估关于激素药物所引起的长期健康效应之因果关系提供了宝贵机遇。

|

||||

和公认的卵巢活动与乳腺癌风险之间关系相关联的是,更年期激素疗法亦可增加更年期、已绝经妇女的乳腺癌发病风险<sup>([乳腺癌激素相关因素合作研究小组, CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19]; [图表][table1])</sup>。单服雌激素、或者合用雌激素与孕激素,皆会增加该风险,而后者增加的幅度更大<sup>([CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19])</sup>。依据近期一项针对所有已有数据的大型荟萃分析,在更年期激素疗法引起的乳腺癌绝对风险上,单服雌激素达 20 年后,发病率将提高约 1.5 倍,而合用雌、孕可提高约 2.5 倍<sup>([CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19])</sup>。因此,合用雌、孕疗法的乳腺癌发病风险高于单服雌激素疗法。在此之前,孕激素因其在乳房中对雌激素的拮抗效应,被认为可能对乳腺癌起抑制作用<sup>([Mauvais-Jarvis, Kuttenn, & Gompel, 1986][MKG86]; [Wren & Eden, 1996][WE96]; [Gompel et al., 2002][G02])</sup>;但上述荟萃分析推翻了该假设。\

|

||||

美国[“妇女健康倡议”][wiki18](WHI)项目似乎也和这种由更年期激素疗法引起的高乳腺癌风险有关系,至少在一项已使用的处方上(即 0.625mg/天的[结合雌激素][wiki19]合并 2.5 mg/天的[醋酸甲羟孕酮][wiki20]方案);使用该疗法 5 年后,发病风险增加 1.25 倍<sup>([WHI 调查员编辑组, WGWHII, 2002][WHI02]; [Chlebowski, Aragaki, & Anderson, 2015][CAA15])</sup>。WHI 是迄今规模最大的激素治疗随机对照试验项目,其为评估关于激素药物所引起的长期健康效应之因果关系提供了宝贵机遇。

|

||||

|

||||

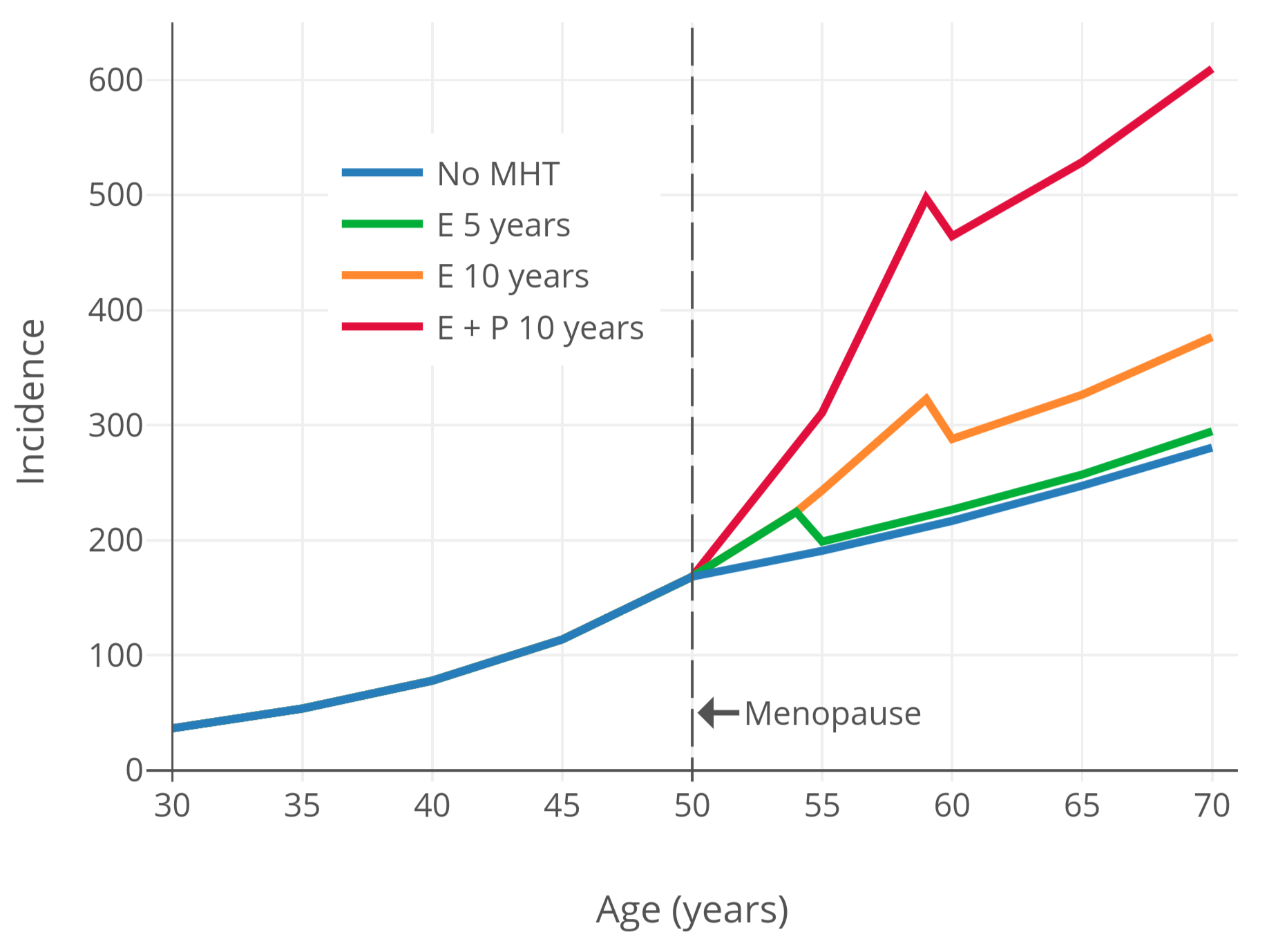

为了将更年期激素疗法引起的乳腺癌风险可视化,下图展示了乳腺癌风险和时间的关系;其基于[“护士健康研究”观察性项目][nhs](NHS)的数据与模型<sup>([Colditz & Rozner, 2000][cr00])</sup>。如图所示,更年期激素疗法可导致乳腺癌风险继续维持指数级增长,而该趋势本应在更年期开始之后减缓。

|

||||

为了将更年期激素疗法引起的乳腺癌风险可视化,下图展示了乳腺癌风险和时间的关系;其基于[“护士健康研究”观察性项目][wiki21](NHS)的数据与模型<sup>([Colditz & Rozner, 2000][CR00])</sup>。如图所示,更年期激素疗法可导致乳腺癌风险继续维持指数级增长,而该趋势本应在更年期开始之后减缓。

|

||||

|

||||

<section class="box">

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

**图 2**:随年龄推移,不同激素治疗状态及类型的已绝经妇女的每十万人中乳腺癌年发生率。本图基于“护士健康研究”观察性项目的数据,使用了泊松回归模型。

|

||||

**图 2**:随年龄推移,不同激素治疗状态及类型的已绝经妇女的每十万人中乳腺癌年发生率<sup>([Colditz & Rozner, 2000][CR00])</sup>。本图基于“[护士健康研究][wiki21]”观察性项目的数据,使用了[泊松回归模型][wiki22]<sup>([Colditz & Rozner, 2000][CR00])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

</section>

|

||||

|

||||

同结合雌激素、醋酸甲羟孕酮等非生物同质性激素药物类似,诸如雌二醇、孕激素等具有生物同质性的激素,也和乳腺癌风险的增长有关<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019; [图表][cghf19-table])</sup>。服用雌二醇所造成的乳腺癌风险,和服用结合雌激素的风险并无二致<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019)</sup>。基于现有数据,口服孕激素(5 年以下)与乳腺癌风险的增长并无关联,这和合成孕酮制剂的情况截然相反<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019; [Stute, Wildt, & Neulen, 2018][swn18]; [Mirkin, 2018][m18]; [Fournier et al., 2007][f07])</sup>。然而,一旦服用超过 5 年,口服孕激素将会助推乳腺癌风险的增长,其增长趋势在幅度上和服用醋酸甲羟孕酮的情况相似<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019; Stute, Wildt, & Neulen, 2018; Mirkin, 2018; Fournier et al., 2007)</sup>。口服孕激素初期相对较低的发病风险,可能与其产生的孕激素水平较低、从而使孕激素效力更低有关<sup>([Kuhl & Schneider, 2013][ks13]; [Davey, 2018][d18]; [维基百科][wiki-1]; [图表][graph-1])</sup>。因此,在口服孕激素引起的乳腺癌风险之增长足以被准确测定之前,可能需要更长的治疗时间(和/或更大的样本规模)<sup>(Kuhl & Schneider, 2013; Davey, 2018)</sup>。\

|

||||

当下对于非口服途径给药的孕激素对乳腺癌风险的影响,尚无任何现有数据提供<sup>(Stute, Wildt, & Neulen, 2018)</sup>。不过,一些研究者预计,无论是长期服用还是短期暴露,非口服途径、有完全效力的孕激素所引起的乳腺癌风险应和合成孕酮制剂相似<sup>(Kuhl & Schneider, 2013; Davey, 2018)</sup>。

|

||||

同结合雌激素、醋酸甲羟孕酮等非生物同质性激素药物类似,诸如雌二醇、孕酮等具有[生物同质性][wiki23]的激素,也和乳腺癌风险的增长有关<sup>([CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19]; [图表][table1])</sup>。服用雌二醇所造成的乳腺癌风险,和服用结合雌激素的风险并无二致<sup>([CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19])</sup>。基于现有数据,口服孕酮(5 年以下)与乳腺癌风险的增长并无关联,这和合成孕酮制剂的情况截然不同<sup>([Aly, 2018][A18-OPLL]; [CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19]; [Stute, Wildt, & Neulen, 2018][SWN18]; [Mirkin, 2018][M18]; [Fournier et al., 2007][F07])</sup>。然而,一旦服用超过 5 年,口服孕酮将会助推乳腺癌风险的增长,其增长趋势在幅度上和服用醋酸甲羟孕酮的情况相似<sup>([Aly, 2018][A18-OPLL]; [CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19]; [Stute, Wildt, & Neulen, 2018][SWN18]; [Mirkin, 2018][M18]; [Fournier et al., 2007][F07])</sup>。口服孕酮初期相对较低的发病风险,可能与其产生的孕酮水平较低、从而使孕激素效力更低有关<sup>([Aly, 2018][A18-OPLL]; [Kuhl & Schneider, 2013][KS13]; [Davey, 2018][D18]; [维基百科][wiki24-oa]; [图表][graph1])</sup>。因此,在口服孕酮引起的乳腺癌风险之增长足以被准确测定之前,可能需要更长的治疗时间(和/或更大的样本规模)<sup>([Aly, 2018][A18-OPLL]; [Kuhl & Schneider, 2013][KS13]; [Davey, 2018][D18])</sup>。\

|

||||

当下对于非口服途径给药的孕酮对乳腺癌风险的影响,尚无任何现有数据提供<sup>([Stute, Wildt, & Neulen, 2018][SWN18])</sup>。不过,一些研究者预计,无论是长期服用还是短期暴露,非口服途径、有完全效力的孕酮所引起的乳腺癌风险应和合成孕酮制剂相似<sup>([Aly, 2018][A18-OPLL]; [Kuhl & Schneider, 2013][KS13]; [Davey, 2018][D18])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

尽管无论是前瞻性观察研究、还是随机对照试验所得到的证据皆表明,更年期妇女单服雌二醇的疗法可增加乳腺癌风险<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019)</sup>;但是已进行的随机对照试验(即 WHI)并未出现单服雌二醇会增加乳腺癌风险的情况,实际上风险反而大幅*降低* 了——相对风险率(RR)0.77,95% 可信区间 0.64-0.93<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019; [图表][cghf19-table2])</sup>。为了解释这种矛盾的现象,一些设想被提了出来。例如,在 WHI 项目的随机对照试验当中贡献了绝大部分数据的女性们有些不寻常之处,表现在其开始激素疗法的年龄较高(平均 64 岁)、超重和肥胖程度较大等<sup>(CGHFBC, 2019; [Kuhl, 2005][k05])</sup>。超重或肥胖的女性已处于更高的乳腺癌风险当中,可能不受单雌激素疗法的进一步影响<sup>(Kuhl, 2005)</sup>。此外,失去雌激素来源已有多年的妇女在接受治疗后可能会对其乳腺癌风险产生反常(paradoxical)的抑制效应,这和从更年期起接受治疗的妇女的情况截然相反;从观测数据亦可见之<sup>([Prentice, 2008][p08]; CGHFBC, 2019)</sup>。这种设想被称为“空档假设(gap hypthesis)”<sup>(Palmieri et al., 2014; [Mueck & Ruan, 2011][mr11])</sup>。\

|

||||

尽管无论是前瞻性观察研究、还是随机对照试验所得到的证据皆表明,更年期妇女单服雌二醇的疗法可增加乳腺癌风险<sup>([CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19])</sup>;但是已进行的随机对照试验(即 WHI)并未出现单服雌二醇会增加乳腺癌风险的情况,实际上风险反而大幅*降低* 了——相对风险率(RR)0.77,95% 可信区间 0.64–0.93<sup>([CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19]; [图表][table2])</sup>。为了解释这种矛盾的现象,一些设想被提了出来。例如,在 WHI 项目的随机对照试验当中贡献了绝大部分数据的女性们有些不寻常之处,表现在其开始激素疗法的年龄较高(平均 64 岁)、超重和肥胖程度较大等<sup>([CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19]; [Kuhl, 2005][K05])</sup>。超重或肥胖的女性已处于更高的乳腺癌风险当中,可能不受单雌激素疗法的进一步影响<sup>([Kuhl, 2005][K05])</sup>。此外,失去雌激素来源已有多年的妇女在接受治疗后可能会对其乳腺癌风险产生反常(paradoxical)的抑制效应,这和从更年期起接受治疗的妇女的情况截然相反;从观测数据亦可见之<sup>([Prentice, 2008][P08]; [CGHFBC, 2019][CGHF19])</sup>。这种设想被称为“[空档假设][wiki25](gap hypthesis)”<sup>([Palmieri et al., 2014][P14]; [Mueck & Ruan, 2011][MR11])</sup>。\

|

||||

为验证这些设想,并查明雌激素对更年期乳腺癌风险的影响,尚需更多随机对照试验支持。

|

||||

|

||||

同样反常的是,在一些其它特定情形下,雌激素和/或孕激素的暴露亦可降低乳腺癌风险、抑制乳腺癌发展。例如,年轻妇女(35 岁以下)如怀孕超过 34 周,在短期(十年内)有更高的乳腺癌风险,但长期(20-25 年以上)风险反而变低了;其终生风险可降低至多 50%<sup>([Nichols et al., 2019][nich19]; [Husby et al., 2018][h18])</sup>。怀孕期间,雌激素与孕激素可达到极高水平(例如,34 周后雌二醇可达 12,500 pg/mL 以上)<sup>([图表][graph-2])</sup>,而这些激素在动物实验当中被认为可起到抑制作用<sup>([Rajkumar et al., 2003][r03])</sup>。对于已绝经 5 年以上的妇女,高剂量雌激素疗法用于治疗乳腺癌很有效,与抗雌激素疗法基本相当<sup>([Bennink et al., 2017][b17])</sup>。与此相反的是,高剂量雌激素疗法对于绝经前妇女的乳腺癌并无作用,尽管其似乎在超大剂量下会起效<sup>(Bennink et al., 2017)</sup>。\

|

||||

然而,雌、孕激素的这些益处只在反常情形下发生(例如超高激素水平/摄入、和/或在性激素不足之前推延之),与女性倾向跨性别者的关系并不密切。无论如何,这些话题都很有趣,笔者考虑将来另作文章来更全面地讨论它们。

|

||||

同样反常的是,在一些其它特定情形下,雌激素和/或孕激素的暴露亦可降低乳腺癌风险、抑制乳腺癌发展。例如,年轻妇女(35 岁以下)如怀孕超过 34 周,在短期(十年内)有更高的乳腺癌风险,但长期(20–25 年以上)风险反而变低了;其终生风险可降低至多 50%<sup>([Nichols et al., 2019][NICH19]; [Husby et al., 2018][H18])</sup>。怀孕期间,雌激素与孕酮可达到极高水平(例如,34 周后雌二醇可达 12,500 pg/mL 以上)<sup>([图表][graph2])</sup>,而这些激素在动物实验当中被认为可起到抑制作用<sup>([Rajkumar et al., 2003][R03]; [Hilakivi-Clarke et al., 2012][HC12])</sup>。对于已绝经 5 年以上的妇女,高剂量雌激素疗法用于治疗乳腺癌很有效,与抗雌激素疗法基本相当<sup>([Bennink et al., 2017][CB17])</sup>。与此相反的是,高剂量雌激素疗法对于绝经前妇女的乳腺癌并无作用,尽管其似乎在超大剂量下会起效<sup>([Bennink et al., 2017][CB17])</sup>。\

|

||||

然而,雌、孕激素的这些益处只在反常情形下发生(例如超高激素水平/摄入、和/或在性激素不足之前推延之),与女性倾向跨性别者的关系并不密切。

|

||||

|

||||

## 男性的雌激素暴露与乳腺癌风险 {#estrogen-exposure-in-men-and-breast-cancer-risk}

|

||||

|

||||

对于顺性别男性,睾酮暴露量较低、和/或雌激素暴露量较高的情形可提高其乳腺癌风险<sup>([Ferzoco & Ruddy, 2016][fr16])</sup>。这些情形包括:睾丸疾病、睾丸被摘除、肝脏疾病等等<sup>(Yousef, 2017)</sup>。其中,睾丸功能障碍、睾丸缺失可导致睾酮暴露量减少;而肝脏疾病会损害雌激素代谢功能,引起雌激素水平上升。此二种情形使得雌激素/雄激素比例增大,从而引起雌激素对乳房更大的刺激作用。乳腺癌风险的增长可能与其存在关联。同样地,男性发生的良性乳房疾病、男性女乳症等等也被发现和乳腺癌风险有关<sup>([Sasco, Lowenfels, & Pasker-De Jong, 1993][slp93])</sup>,不过这些发现跟男性女乳症的风险混淆了<sup>([Giordano, 2005][g05])</sup>。除健康状况之外,顺性别男性用于治疗前列腺癌的高剂量雌激素疗法也被发现与乳腺癌风险的增加有关<sup>([Thellenberg et al., 2003][t03]; [Karlsson et al., 2006][k06])</sup>。

|

||||

对于顺性别男性,睾酮暴露量较低、和/或雌激素暴露量较高的情形可提高其乳腺癌风险<sup>([Ferzoco & Ruddy, 2016][FR16])</sup>。这些情形包括:睾丸疾病、睾丸被摘除、肝脏疾病等等<sup>([Abdelwahab Yousef, 2017][AY17])</sup>。其中,睾丸功能障碍、睾丸缺失可导致睾酮暴露量减少;而肝脏疾病会损害雌激素代谢功能,引起雌激素水平上升。此二种情形使得雌激素/雄激素比例增大,从而引起雌激素对乳房更大的刺激作用。乳腺癌风险的增长可能与其存在关联。同样地,男性发生的良性乳房疾病、男性女乳症等等也被发现和乳腺癌风险有关<sup>([Sasco, Lowenfels, & Pasker-De Jong, 1993][SLP93])</sup>,不过这些发现跟男性女乳症的风险混淆了<sup>([Giordano, 2005][G05])</sup>。除健康状况之外,顺性别男性用于治疗前列腺癌的高剂量雌激素疗法也被发现与乳腺癌风险的增加有关<sup>([Thellenberg et al., 2003][T03]; [Karlsson et al., 2006][K06])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

## 关于女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险的研究项目 {#studies-of-breast-cancer-risk-in-transfeminine-people}

|

||||

|

||||

本文将现有与女性化激素疗法引起的乳腺癌风险有关的研究项目,列入一份 Google 文档附件,其可于[此处][app-1]查阅。截至目前,已有三个大型群体、数个较小群体研究评估了女性化激素治疗引起的乳腺癌风险。

|

||||

本文有一份附件列出了现有与女性化激素疗法引起的乳腺癌风险有关的研究项目,其可于[此处][appendix1]查阅。截至目前,已有三个大型群体、数个较小群体研究评估了女性化激素治疗引起的乳腺癌风险。

|

||||

|

||||

### 阿姆斯特丹自由大学医学中心(VUMC)的研究 {#veterans-health-administration-vha-study}

|

||||

|

||||

附件中大部分研究项目由荷兰的阿姆斯特丹自由大学医学中心(VUMC)进行<sup>([Asscheman, Gooren, & Eklund, 1989][age89]; [van Kesteren et al., 1997][k97]; [Mueller & Gooren, 2008][mg08]; [Asscheman et al., 2011][a11]; [Gooren et al., 2013][g13]; [de Blok et al., 2018][b18]; [de Blok et al., 2019][b19])</sup>。该诊所为荷兰 95% 的跨性别者提供治疗<sup>(de Blok et al., 2019)</sup>。VUMC 的研究项目均大致基于同一批持续变化(evolving)的跨性别女性群体。数十年间,VUMC 仅报告了很低的乳腺癌发生率,并不比顺性别男性的高出许多——经过平均约 20 年的激素治疗,2300 名跨性别女性当中仅报告两起乳腺癌病例<sup>(Gooren et al., 2013)</sup>。该诊所通常采用的处方,是雌激素合并高剂量醋酸环丙孕酮。\

|

||||

这些项目并未对乳腺癌做系统性筛查,对乳腺癌的诊断大都依赖于病人的报告,因此存在病例漏检的可能性<sup>([Feldman et al., 2016][f16])</sup>。

|

||||

附件中大部分研究项目由荷兰的[阿姆斯特丹自由大学医学中心][wiki26](VUMC)进行<sup>([Asscheman, Gooren, & Eklund, 1989][AGE89]; [van Kesteren et al., 1997][VK97]; [Mueller & Gooren, 2008][MG08]; [Asscheman et al., 2011][A11]; [Gooren et al., 2013][G13]; [de Blok et al., 2018][DB18]; [de Blok et al., 2019][DB19])</sup>。该诊所为荷兰 95% 的跨性别者提供治疗<sup>([de Blok et al., 2019][DB19])</sup>。VUMC 的研究项目均大致基于同一批持续变化(evolving)的跨性别女性群体。数十年间,VUMC 仅报告了很低的乳腺癌发生率,并不比顺性别男性的高出许多——经过平均约 20 年的激素治疗,2300 名跨性别女性当中仅报告两起乳腺癌病例<sup>([Gooren et al., 2013][G13])</sup>。该诊所通常采用的处方,是雌激素合并高剂量醋酸环丙孕酮。\

|

||||

这些项目并未对乳腺癌做系统性筛查,对乳腺癌的诊断大都依赖于病人的报告,因此存在病例漏检的可能性<sup>([Feldman et al., 2016][F16])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

2019 年,VUMC 又进行了一项跟踪性研究,不过这次使用了新的方式获得乳腺癌诊断史<sup>(de Blok et al., 2019)</sup>。研究者不再单纯询问病人是否被诊断出乳腺癌,而是通过遍及荷兰的一套电子病历信息系统:“[荷兰国家病理学/解剖学自动化档案馆][palga](PALGA)”来获取乳腺癌诊断史。这样一来,其报告的乳腺癌病例数从 2 例跃升至 15 例。这使得接受激素治疗平均达 15 年左右之后的乳腺癌相对风险率,相较先前期望的几乎翻了 50 倍之多,而绝对发生率约达 0.6%。这项发现推翻了该诊所早前所有研究的结论,也表明在早前研究中,VUMC 治疗的群体的乳腺癌真实病例数被大幅低估。可以认为,诸如肺癌风险、以及在本项研究骤增近 50 倍的乳腺癌病例等健康风险的大幅增长,应是符合逻辑的。故此,研究者以严谨行文,对这种增长做了详细描述<sup>(de Blok et al., 2019; [Reactions Weekly, 2019][rw19])</sup>。\

|

||||

在此之前,女性化激素疗法所引起的乳腺癌风险之增长被认为很低,而今新的数据证明了其不一定属实<sup>([de Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019][bdh19])</sup>。

|

||||

2019 年,VUMC 又进行了一项跟踪性研究,不过这次使用了新的方式获得乳腺癌诊断史<sup>([de Blok et al., 2019][DB19])</sup>。研究者不再单纯询问病人是否被诊断出乳腺癌,而是通过遍及荷兰的一套电子病历信息系统:“[荷兰国家病理学/解剖学自动化档案馆][palga](PALGA)”来获取乳腺癌诊断史。这样一来,其报告的乳腺癌病例数从 2 例跃升至 15 例。这使得接受激素治疗平均达 15 年左右之后的乳腺癌相对风险率,相较先前期望的几乎翻了 50 倍之多,而绝对发生率约达 0.6%。这项发现推翻了该诊所早前所有研究的结论,也表明在早前研究中,VUMC 治疗的群体的乳腺癌真实病例数被大幅低估。可以认为,诸如肺癌风险、以及在本项研究骤增近 50 倍的乳腺癌病例等健康风险的大幅增长,应是符合逻辑的。故此,研究者以严谨行文,对这种增长做了详细描述<sup>([de Blok et al., 2019][DB19]; [*Reactions Weekly*, 2019][RW19])</sup>。\

|

||||

在此之前,女性化激素疗法所引起的乳腺癌风险之增长被认为很低,而今新的数据证明了其不一定属实<sup>([de Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019][BDH19])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

### 美国退伍军人卫生管理局(VHA)的研究

|

||||

|

||||

另一组大型群体来自美国退伍军人卫生管理局(VHA)<sup>([Brown & Jones, 2015][bj15]; [Brown, 2015][b15])</sup>。2015 年,一篇采用该群体数据的研究论文被发表。其中,研究者报告了在平均跟踪大约 10 年之后,出生指派性别为男的约 3500 人当中有 3 例乳腺癌病例。也就是说,平均治疗时长达 10 年时,发病率约为 0.09%。尽管其在平均跟踪时长上比 VUMC 的群体更短,但在总时长上与后者相近。VHA 的研究者还报告,乳腺癌发生率较先前预计的增长 33 倍。有些奇怪的是,其和 VUMC 于 2018 年报告的 46 倍并不一致(后者基于 2,300 人平均跟踪 15 年后有 15 人被确诊的事实)。VHA 总结认为,无论如何,女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险高于顺性别男性、也高于 VUMC 早前所报告的,但仍低于顺性别妇女。

|

||||

另一组大型群体来自[美国退伍军人卫生管理局][wiki27](VHA)<sup>([Brown & Jones, 2015][BJ15]; [Brown, 2015][B15])</sup>。2015 年,一篇采用该群体数据的研究论文被发表。其中,研究者报告了在平均跟踪大约 10 年之后,出生指派性别为男的约 3500 人当中有 3 例乳腺癌病例。也就是说,平均治疗时长达 10 年时,发病率约为 0.09%。尽管其在平均跟踪时长上比 VUMC 的群体更短,但在总时长上与后者相近。VHA 的研究者还报告,乳腺癌发生率较先前预计的增长 33 倍。有些奇怪的是,其和 VUMC 于 2018 年报告的 46 倍并不一致(后者基于 2,300 人平均跟踪 15 年后有 15 人被确诊的事实)。VHA 总结认为,无论如何,女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险高于顺性别男性、也高于 VUMC 早前所报告的,但仍低于顺性别妇女。

|

||||

|

||||

VHA 的论文并未披露在激素疗法当中使用的药物及其剂量,不过考虑到其囊括了接受 VHA 系统的服务提供者治疗的所有患者,其处方应当千差万别。既然是在美国,通常的处方应该是雌激素合并螺内酯,无孕激素。

|

||||

|

||||

VHA 的研究项目有一些问题需要探讨:

|

||||

|

||||

- 同 VUMC 早前的研究项目一样,VHA 的研究也未对乳腺癌做系统性筛查,其诊断乳腺癌基本依赖病人的报告,从而存在病例漏检的可能性<sup>(Feldman et al., 2016)</sup>。

|

||||

- 该项目*未将激素疗法纳入考虑* <sup>(Feldman et al., 2016)</sup>。VHA 患者群体中只有少部分人正接受激素治疗,研究者并不知道多少人在接受治疗、多少人没有。此外,该群体中甚至有不明比例的人*不是跨性别者* ——研究者将 VHA 系统当中有“跨性别相关”诊断史(如“异装癖”,即变装者)的所有顺性别男性囊括其中。这些个体的绝大部分应当皆未接受激素治疗。

|

||||

- 同 VUMC 早前的研究项目一样,VHA 的研究也未对乳腺癌做系统性筛查,其诊断乳腺癌基本依赖病人的报告,从而存在病例漏检的可能性<sup>([Feldman et al., 2016][F16])</sup>。

|

||||

- 该项目*未将激素疗法纳入考虑* <sup>([Feldman et al., 2016][F16])</sup>。VHA 患者群体中只有少部分人正接受激素治疗,研究者并不知道多少人在接受治疗、多少人没有。此外,该群体中甚至有不明比例的人不是真的跨性别者——研究者将 VHA 系统当中有“跨性别相关”诊断史(如“异装癖”,或变装者)的所有顺性别男性囊括其中。这些个体的绝大部分应当皆未接受激素治疗。

|

||||

- 对明确正接受激素治疗的人群的跟踪时长过短。在 VHA 患者群体当中,约有 1400 名明确正接受激素治疗的女性倾向跨性别者;对其的平均跟踪时长仅有 5.5 年,而其中近半数个体的跟踪时长尚未达 3 年。

|

||||

- VHA 的论文内容很不明晰,令人费解。例如,VHA 对跨性别者的称谓有误,按其出生时的性别“男性”或“女性”指代之并行文,如此很难分辨出谁是谁、谁在接受激素治疗与否。不仅如此,连一些针对该研究项目的评述文章也在讨论“男性”与“女性”的风险时错误地倒置身份<sup>(例如 [Dente et al., 2019][d19])</sup>。

|

||||

- 还有一点令人费解:VHA 研究者在相同时间点前后发表的两篇论文里,报告了包含出生指派性别为男、女的 5100 人的群体(两篇所指为同一组)出现 _33_ 例乳腺癌病例<sup>([Brown & Jones, 2014][bj14]; [Brown & Jones, 2016][bj16])</sup>。作为对比,他们在 2015 年的论文中仅报告了 10 例(其中 3 例出生指派性别为男、7 例则为女)。造成这种差异的原因尚不清楚<sup>([Braun et al., 2017][braun17])</sup>。

|

||||

- VHA 的论文内容很不明晰,令人费解。例如,VHA 对跨性别者的称谓有误,按其出生时的性别“男性”或“女性”指代之并行文,如此很难分辨出谁是谁、谁在接受激素治疗与否。不仅如此,连一些针对该研究项目的评述文章也在讨论“男性”与“女性”的风险时错误地倒置身份<sup>(例如 [Dente et al., 2019][D19])</sup>。

|

||||

- 还有一点令人费解:VHA 研究者在相同时间点(2015 年)前后发表的两篇论文里,报告了包含出生指派性别为男、女的 5100 人的群体(两篇所指为同一组)出现 _33_ 例乳腺癌病例<sup>([Brown & Jones, 2014][BJ14]; [Brown & Jones, 2016][BJ16])</sup>。作为对比,他们在 2015 年的论文中仅报告了 10 例(其中 3 例出生指派性别为男、7 例则为女)。造成这种差异的原因尚不清楚<sup>([Braun et al., 2017][B17])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

出于上述问题的缘故,VHA 的项目的参考价值有限,应谨慎对待。VUMC 在 2019 年发表的数据远比其更具有价值。

|

||||

出于上述问题的缘故,VHA 的项目的参考价值有限,可能要谨慎对待。VUMC 在 2019 年发表的资料远比其更具有价值。

|

||||

|

||||

### 凯撒医疗集团在加州和乔治亚州的研究 {#kaiser-permanente-in-california-and-georgia-study}

|

||||

|

||||

第三组、也是最后一组群体研究,来自[凯撒医疗集团][kais](Kaiser Permanente)在美国北加利福尼亚州、南加州和乔治亚州的分站<sup>([Silverberg et al., 2017][s17])</sup>。他们报告了来自上述三处分站、总计约 2800 名女性倾向跨性别者组成的群体的不同癌症发生率。对该群体的平均跟踪时长只有 4 年。研究者并未报告任何发生不足 5 例的癌症病例;而女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌既未出现在相关结果图表,亦未于讨论环节当中被提及。故此,该群体的乳腺癌病例应该少于 5 例。然而,由研究者 T’Sjoen 及其同行组成的跨性别医学研究领域权威团队,在其文章中援引凯撒集团的论文时指出,凯撒集团的团队发现了女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险较顺性别男性更高、但较顺性别女性更低<sup>([T’Sjoen et al., 2019][ts19])</sup>。如果此言属实(目前来看有很大概率),那么其应该是从和凯撒集团的研究者的私下交流当中取得的。\

|

||||

第三组、也是最后一组群体研究,来自[凯撒医疗集团][wiki28](Kaiser Permanente)在美国北加利福尼亚州、南加州和乔治亚州的分站<sup>([Silverberg et al., 2017][S17])</sup>。他们报告了来自上述三处分站、总计约 2800 名女性倾向跨性别者组成的群体的不同癌症发生率。对该群体的平均跟踪时长只有 4 年。研究者并未报告任何发生不足 5 例的癌症病例;而女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌既未出现在相关结果图表,亦未于讨论环节当中被提及。故此,该群体的乳腺癌病例应该少于 5 例。然而,由研究者 T’Sjoen 及其同行组成的跨性别医学研究领域权威团队,在其文章中援引凯撒集团的论文时指出,凯撒集团的团队发现了女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险较顺性别男性更高、但较顺性别女性更低<sup>([T’Sjoen et al., 2019][TS19])</sup>。如果此言属实(目前来看有很大概率),那么其应该是从和凯撒集团的研究者的私下交流当中取得的。\

|

||||

凯撒集团的研究存在一定局限性,包括缺乏对乳腺癌风险的准确估计数字,以及跟踪时长非常短,等等。此外,癌症诊断史仅取自凯撒集团自有的信息系统;对于其癌症筛查的系统性如何,也尚不清楚。

|

||||

|

||||

凯撒集团的研究者计划进行的研究项目,将通过将其拓展至其它分站来扩大患者群体规模<sup>(Silverberg et al., 2017)</sup>。这种改进令人振奋,其有望提供更多和跨性别者健康风险有关的数据,包括乳腺癌风险。

|

||||

凯撒集团的研究者计划进行的研究项目,将通过将其拓展至其它分站来扩大患者群体规模<sup>([Silverberg et al., 2017][S17])</sup>。这种改进令人振奋,其有望提供更多和跨性别者健康风险有关的数据,包括乳腺癌风险。

|

||||

|

||||

### 其它较小的群体研究 {#small-cohort-studies}

|

||||

|

||||

其余的针对女性倾向跨性别者之乳腺癌风险的科研项目规模均较小。其中一项是由比利时根特大学进行的,其跟踪了 50 名已进行性别重置手术的跨性别女性,平均跟踪时长 11.4 年;其未报告任何乳腺癌病例<sup>([Wierckx et al., 2012][w12])</sup>。另一项是由德国埃朗根大学医院进行的,其跟踪了 60 名跨性别女性;其同样未报告任何病例,不过她们的治疗时长仅有两年<sup>([Dittrich et al., 2005][d05])</sup>。最后一项是由 [Harry Benjamin][wiki-2] 医生进行的;他在 1960 年代发表的文章里透露,其已为大约 150 名跨性别女性提供“中等至较大剂量的雌激素”治疗,期限从 3 个月到 12 年不等;其未曾接触到乳腺癌病例<sup>([Benjamin, 1964][b64]; [Benjamin, 1966][b66]; Gooren et al., 2013)</sup>。\

|

||||

其余的针对女性倾向跨性别者之乳腺癌风险的科研项目规模均较小。其中一项是由比利时根特大学进行的,其跟踪了 50 名已进行性别重置手术的跨性别女性,平均跟踪时长 11.4 年;其未报告任何乳腺癌病例<sup>([Wierckx et al., 2012][W12])</sup>。另一项是由德国埃朗根大学医院进行的,其跟踪了 60 名跨性别女性;其同样未报告任何病例,不过她们的治疗时长仅有两年<sup>([Dittrich et al., 2005][D05])</sup>。最后一项是由 [Harry Benjamin][wiki29] 医生进行的;他在 1960 年代发表的文章里透露,其已为大约 150 名跨性别女性提供“中等至较大剂量的雌激素”治疗,期限从 3 个月到 12 年不等;其未曾接触到乳腺癌病例<sup>([Benjamin, 1964][B64]; [Benjamin, 1966][B66]; [Gooren et al., 2013][G13])</sup>。\

|

||||

上述群体规模太小,难以对女性倾向跨性别者之乳腺癌风险进行有意义的量化。

|

||||

|

||||

### 关于既有研究项目的讨论 {#discussion-of-the-available-studies}

|

||||

|

||||

#### 由跟踪时长过短导致的对乳腺癌风险之量化的不确定性 {#inconclusive-quantification-of-breast-cancer-risk-due-to-short-follow-up-times}

|

||||

|

||||

由于跟踪时长不足,关于女性倾向跨性别者之乳腺癌风险的现有研究项目的结论并不充分<sup>(de Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019; Mueller & Gooren, 2008; [Gooren, 2011][g11]; Gooren et al., 2013; Brown & Jones, 2015)</sup>。例如,在 VUMC 和 VHA 的研究里,平均跟踪时长仅有 10-20 年。对于顺性别妇女,其乳腺癌风险在停经前的数十年里呈指数级增长,但到了老年,增幅会非常低。顺性别妇女通常被确诊乳腺癌的年龄为 60 岁,这 60 年里包括停经前的 50 年激素暴露量、和绝经后 10 年的激素暴露量;如上文所示,这后 10 年里接受预防性抗雌激素疗法可大幅降低乳腺癌风险,因此其重要性不容忽视。综上,由于现有关于女性化激素疗法与乳腺癌风险的研究的跟踪时长过短,迄今尚不清楚我们(女性倾向跨性别者)真实的、或者说终生的乳腺癌风险到底如何<sup>(Mueller & Gooren, 2008)</sup>。

|

||||

由于跟踪时长不足,关于女性倾向跨性别者之乳腺癌风险的现有研究项目的结论并不充分<sup>([de Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019][BDH19]; [Mueller & Gooren, 2008][MG08]; [Gooren, 2011][G11]; [Gooren et al., 2013][G13]; [Brown & Jones, 2015][BJ15])</sup>。例如,在 VUMC 和 VHA 的研究里,平均跟踪时长仅有 10–20 年。对于顺性别妇女,其乳腺癌风险在停经前的数十年里呈指数级增长,但到了老年,增幅会非常低。顺性别妇女通常被确诊乳腺癌的年龄为 60 岁,这 60 年里包括停经前的 50 年激素暴露量、和绝经后 10 年的激素暴露量;如上文所示,这后 10 年里接受预防性抗雌激素疗法可大幅降低乳腺癌风险,因此其重要性不容忽视。综上,由于现有关于女性化激素疗法与乳腺癌风险的研究的跟踪时长过短,迄今尚不清楚女性倾向跨性别者真实的、或者说终生的乳腺癌风险到底如何<sup>([Mueller & Gooren, 2008][MG08])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

不过我们已知的是,女性倾向跨性别者在使用激素疗法(至少也有一种雌激素、一种形如醋酸环丙孕酮的孕激素)约 15 年后,其乳腺癌风险显然会大幅增加<sup>(de Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019)</sup>。好在,其风险处于顺性别妇女和顺性别男性之间,并不会高于顺性别妇女。然而与此同时,其风险仍不容忽视,绝对发生率也必然随着跟踪时间延长而增大。\

|

||||

关于终生风险,至少从 de Blok 等人 (2019) 的发现及其使用的激素治疗处方来看,女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌发生率大约就在几个百分点之多。

|

||||

不过我们已知的是,女性倾向跨性别者在使用激素疗法(至少也有一种雌激素、一种形如醋酸环丙孕酮的孕激素)约 15 年后,其乳腺癌风险显然会大幅增加<sup>([de Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019][BDH19])</sup>。好在,其风险处于顺性别妇女和顺性别男性之间,并不会高于顺性别妇女。然而与此同时,其风险仍不容忽视,绝对发生率也必然随着跟踪时间延长而增大。\

|

||||

关于终生风险,至少从 [de Blok 等人 (2019)][DB19] 的发现及其使用的激素治疗处方来看,女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌发生率大约就在几个百分点之多。

|

||||

|

||||

#### 和终生激素暴露量相关的乳腺癌风险 {#breast-cancer-risk-in-relation-to-lifetime-hormone-exposure}

|

||||

|

||||

女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险应该低于顺性别妇女。这可能至少出于前者的终生激素暴露量更少的缘故<sup>(Mueller & Gooren, 2008)</sup>。事实上,至少从历史来看,女性倾向跨性别者开始接受激素治疗的平均年龄在 30-40 岁,而该年龄距离顺性别女性通常经历青春期的年龄段已过去数十年<sup>(Mueller & Gooren, 2008)</sup>。此外,青年人群可能在特定时间段里对乳腺癌易感<sup>([Biro & Wolff, 2011][bw11]; [Biro & Deardorff, 2013][bd13]; [Biro et al., 2020][b20])</sup>。然而,近年来女性倾向跨性别者启动激素治疗的年龄正在降低<sup>(Mueller & Gooren, 2008)</sup>,如今有不少人在十几到二十来岁便开始服用激素了。相较于早年里服用激素更晚的个体,这些个体的终生激素暴露量会更大,其乳腺癌风险也会更高。而且,到了顺性别妇女通常的更年期年龄,女性倾向跨性别者很少有意停止激素治疗<sup>(Mueller & Gooren, 2008)</sup>;其中许多人终其一生皆会维持治疗。这种额外的激素暴露量会使乳腺癌风险进一步升高<sup>(Mueller & Gooren, 2008)</sup>。

|

||||

女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌风险应该低于顺性别妇女。这可能至少出于前者的终生激素暴露量更少的缘故<sup>([Mueller & Gooren, 2008][MG08])</sup>。事实上,至少从历史来看,女性倾向跨性别者开始接受激素治疗的平均年龄在 30-40 岁,而该年龄距离顺性别女性通常经历青春期的年龄段已过去数十年<sup>([Mueller & Gooren, 2008][MG08])</sup>。此外,青年人群可能在特定时间段里对乳腺癌易感<sup>([Biro & Wolff, 2011][BW11]; [Biro & Deardorff, 2013][BD13]; [Biro et al., 2020][B20])</sup>。然而,近年来女性倾向跨性别者启动激素治疗的年龄正在降低<sup>([Mueller & Gooren, 2008][MG08])</sup>,如今有不少人在十几到二十来岁便开始服用激素了。相较于早年里服用激素更晚的个体,这些个体的终生激素暴露量会更大,其乳腺癌风险也会更高<sup>([Sutherland et al., 2020][S20])</sup>。而且,到了顺性别妇女通常的更年期年龄,女性倾向跨性别者很少有意停止激素治疗<sup>([Mueller & Gooren, 2008][MG08])</sup>;其中许多人终其一生皆会维持治疗。这种额外的激素暴露量会使乳腺癌风险进一步升高<sup>([Mueller & Gooren, 2008][MG08])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

#### 和孕激素及其剂量相关的乳腺癌风险 {#breast-cancer-risk-in-relation-to-progestogens-and-dosage}

|

||||

|

||||

现有的发现表明,顺性别妇女合并使用雌、孕激素时的乳腺癌风险,要高于单用雌激素;由此可以类推,女性倾向跨性别者合用雌、孕激素的激素疗法也会有更高的乳腺癌风险<sup>(Mde Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019)</sup>。有这样一种可能:相较于已被 VUMC 研究过的合用雌激素与醋酸环丙孕酮疗法,如排除掉孕激素、仅用雌激素,则乳腺癌风险兴许会更低<sup>(Mde Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019)</sup>。另外需要注意的是,VUMC 所用醋酸环丙孕酮的剂量会使得孕激素暴露量相当之高<sup>([Aly, 2019][aw19-cd])</sup>。\

|

||||

乳腺癌风险与孕激素剂量之间的关联程度,目前尚不明确。类似地,乳腺癌风险是否受雌激素剂量影响,以及高雌激素剂量下是否有更高风险,目前也不明确。但无论如何,有绝经前妇女合用雌、孕激素的避孕疗法会增加乳腺癌风险的事实在先,可以认为,较高的雌/孕激素暴露量会增加一定程度的乳腺癌风险<sup>([Kahlenborn et al,, 2006][kahl06]; [Zhu et al., 2012][z12]; [Ji et al., 2019][j19])</sup>。\

|

||||

另外,一项早年的调查性研究显示,绝经前妇女使用雌激素注射剂之后,乳腺癌风险相较口服雌激素、或未服用激素者增加了 4 倍<sup>([Hulka et al., 1982][h82]; [Coe & Parks, 1989][cp89])</sup>。需要注意,通常剂量的雌激素注射剂所提供的雌激素暴露量,是远大于口服雌激素和其它给药途径的<sup>([Göretzlehner et al., 2002][gore02]; [Aly, 2021][aw21-iema])</sup>。

|

||||

现有的发现表明,顺性别妇女合并使用雌、孕激素时的乳腺癌风险,要高于单用雌激素;由此可以类推,女性倾向跨性别者合用雌、孕激素的激素疗法也会有更高的乳腺癌风险<sup>([de Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019][BDH19])</sup>。有这样一种可能:相较于已被 VUMC 研究过的合用雌激素与醋酸环丙孕酮疗法,如排除掉孕激素、仅用雌激素,则乳腺癌风险兴许会更低<sup>([de Blok, Dreijerink, & Heijer, 2019][BDH19])</sup>。另外需要注意的是,VUMC 所用醋酸环丙孕酮的剂量会使得孕激素暴露量相当之高<sup>([Aly, 2019][A19-CD])</sup>。\

|

||||

乳腺癌风险与孕激素剂量之间的关联程度,目前尚不明确。类似地,乳腺癌风险是否受雌激素剂量影响,以及高雌激素剂量下是否有更高风险,目前也不明确。但无论如何,有绝经前妇女使用[雌、孕激素复方避孕疗法][wiki30]会增加乳腺癌风险的事实在先,可以认为,较高的雌/孕激素暴露量会增加一定程度的乳腺癌风险<sup>([Kahlenborn et al., 2006][KAHL06]; [Zhu et al., 2012][Z12]; [Ji et al., 2019][J19])</sup>。\

|

||||

另外,一项早年的调查性研究显示,绝经前妇女使用雌激素注射剂之后,乳腺癌风险相较口服雌激素、或未服用激素者增加了 4 倍<sup>([Hulka et al., 1982][H82]; [Coe & Parks, 1989][CP89])</sup>。需要注意,通常剂量的雌激素注射剂所提供的雌激素暴露量,是远大于口服雌激素和其它给药途径的<sup>([Göretzlehner et al., 2002][GORE02]; [Aly, 2021][A21-IEMA])</sup>。但是,该研究存在很大的局限性:包括同类型研究仅此一项,年份非常早,等等。

|

||||

|

||||

## X 染色体与乳腺癌风险 {#x-chromosomes-and-breast-cancer-risk}

|

||||

|

||||

人类性染色体包括 X 染色体和 Y 染色体。顺性别妇女通常有两条 X 染色体(即 46,XX 核型);而顺性别男性、女性倾向跨性别者通常有一条 X 染色体、一条 Y 染色体(即 46,XY 核型)。其中 46,XX 核型(即第二条 X 染色体的存在)可能会是乳腺癌风险的主要因素。X 染色体的获得(非整倍性)、以及其异常失活,已被发现和乳腺癌的发生及发展有关<sup>([Nakopoulou et al., 2007][n07]; [Di Oto et al., 2015][do15]; [Lin et al., 2015][l15]; [Chaligné et al., 2015][c15]; [Di Oto et al., 2018][do18])</sup>。此外,患有克氏综合征(即核型为 46,XXY)的男性的乳腺癌风险,也比 46,XY 核型的正常男性要高。\

|

||||

与此相反的是,患有完全性雄激素不敏感综合征(CAIS)的女性,迄今未有乳腺癌病例报告——这还是在她们的乳房发育良好的情况下<sup>([Aly, 2020][aw20])</sup>;其核型为 46,XY ,和女性倾向跨性别者相同<sup>([Hughes et al., 2012][h12]; [Tiefenbacher & Daxenbichler, 2008][td08]; [Hughes, 2009][h09])</sup>。不过,克氏综合征与 CAIS 患者体内的激素异常现象,在乳腺癌风险上的作用可能有所不同,从而会造成一定迷惑性。尤其需要注意的是,患 CAIS 的女性的雌激素暴露量较少,体内孕激素也极少、以至不存在。无论如何,对于克氏综合征与 CAIS 患者的乳腺癌风险之差异,无法完全用激素异常来解释。\

|

||||

综上,可以认为,女性倾向跨性别者*体内第二条 X 染色体的缺少*\*,的确可能会在一定程度上降低乳腺癌风险。针对本话题有更深入的讨论,详见[此处][app-2]。

|

||||

人类[性染色体][wiki31]包括 [X 染色体][wiki32]和 [Y 染色体][wiki33]。顺性别妇女通常有两条 X 染色体(即 46,XX [核型][wiki34]);而顺性别男性、女性倾向跨性别者通常有一条 X 染色体、一条 Y 染色体(即 46,XY 核型)。其中 46,XX 核型(即第二条 X 染色体的存在)可能会是乳腺癌风险的主要因素。X 染色体的获得([非整倍性][wiki35])、以及其异常[失活][wiki36],已被发现和乳腺癌的发生及发展有关<sup>([Nakopoulou et al., 2007][N07]; [Di Oto et al., 2015][DO15]; [Lin et al., 2015][L15]; [Chaligné et al., 2015][C15]; [Di Oto et al., 2018][DO18])</sup>。此外,患有[克氏综合征][wiki37](即核型为 46,XXY)的男性的乳腺癌风险,也比 46,XY 核型的正常男性要高。\

|

||||

与此相反的是,患有[完全性雄激素不敏感综合征][wiki38](CAIS)的女性,迄今未有乳腺癌病例报告——这还是在她们的乳房发育良好的情况下<sup>([Aly, 2020][A20-CBDP])</sup>;其核型为 46,XY ,和女性倾向跨性别者相同<sup>([Hughes et al., 2012][H12]; [Tiefenbacher & Daxenbichler, 2008][TD08]; [Hughes, 2009][H09])</sup>。不过,克氏综合征与 CAIS 患者体内的激素异常现象,在乳腺癌风险上的作用可能有所不同,从而会造成一定迷惑性。尤其需要注意的是,患 CAIS 的女性的雌激素暴露量较少,体内孕酮也极少、以至不存在。无论如何,对于克氏综合征与 CAIS 患者的乳腺癌风险之差异,无法完全用激素异常来解释。\

|

||||

综上,可以认为,女性倾向跨性别者*体内第二条 X 染色体的缺少*\*,的确可能会在一定程度上降低乳腺癌风险。针对本话题有更深入的讨论,详见此[附件][appendix2]。

|

||||

|

||||

> _\* 译者注:原文为“缺少的两条 X 染色体”(the lack of two X chromosomes)。_

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -150,128 +156,286 @@ VHA 的研究项目有一些问题需要探讨:

|

|||

早年有关女性化激素疗法与乳腺癌风险的研究发现,女性倾向跨性别者的乳腺癌发生率很低。然而,近期的一项研究采用了更好的研究方法,其发现的乳腺癌风险增加了近 50 倍。其患者群体所用的激素治疗处方,仅为雌激素合并醋酸环丙孕酮。目前尚不清楚其它激素处方(如单用雌激素,或雌激素合并非甾体类抗雄制剂)是否会有相似的风险。由于跟踪时长不足,有关女性倾向跨性别者之乳腺癌风险的现有数据存在局限性。因此,其终生乳腺癌风险尚未可知。\

|

||||

不过基于现有数据,可以预测未来的情况,即女性倾向跨性别者的终生乳腺癌风险率应有几个百分点之高。该风险率处于顺性别男性和顺性别妇女之间。

|

||||

|

||||

女性化激素疗法引起的乳腺癌风险会受到不同因素的影响。例如,累计用药时长,开始治疗的年龄,孕激素的长期服用,以及(可能的)雌/孕激素剂量,等等。我们(女性倾向跨性别者)体内第二条 X 染色体的缺少也许对乳腺癌起到了部分抑制作用。\

|

||||

尽管女性化激素疗法引起的乳腺癌风险是有必要予以关注的——特别是考虑到孕激素在其中的促进作用——,但放眼长期,乳腺癌的终生发生率应该很低,其风险显然也低于顺性别妇女。此外,乳腺癌的发生也需要经过长达多年的激素暴露,其一般也仅出现在老年。而且,乳腺癌容易治疗,患者生存时长可达 5-10 年。综上,基本可以肯定,考虑乳腺癌时不应将女性化激素疗法的情况排除在外。

|

||||

女性化激素疗法引起的乳腺癌风险会受到不同因素的影响。例如,累计用药时长,开始治疗的年龄,孕激素的长期服用,以及(可能的)雌/孕激素剂量,等等。女性倾向跨性别者体内第二条 X 染色体的缺少也许对乳腺癌起到了部分抑制作用。\

|

||||

尽管女性化激素疗法引起的乳腺癌风险是有必要引起女性倾向跨性别者关注的(特别是考虑到孕激素在其中的促进作用),但放眼长期,乳腺癌的终生发生率应该很低,其风险显然也低于顺性别妇女。此外,乳腺癌的发生也需要经过长达多年的激素暴露,其一般也仅出现在老年。而且,乳腺癌容易治疗,患者生存时长可达 5-10 年<sup>([Cancer.Net][CANCER20])</sup>。综上,基本可以肯定,考虑乳腺癌时不应将女性化激素疗法的情况排除在外。

|

||||

|

||||

女性化激素疗法引起乳腺癌的可能性,倒是凸显了对年龄与激素暴露量符合标准的女性倾向跨性别者定期进行乳腺癌筛查的重要性<sup>([Chowdhry & O’Connell, 2020][co20])</sup>。在此建议长期进行激素治疗的女性倾向跨性别者,也像顺性别妇女的过程一样接受乳腺癌筛查<sup>(Chowdhry & O’Connell, 2020)</sup>。

|

||||

女性化激素疗法引起乳腺癌的可能性,倒是凸显了对年龄与激素暴露量符合标准的女性倾向跨性别者定期进行乳腺癌筛查的重要性<sup>([Chowdhry & O’Connell, 2020][CO20])</sup>。应当建议长期进行激素治疗的女性倾向跨性别者,也像顺性别妇女的过程一样接受乳腺癌筛查<sup>([Chowdhry & O’Connell, 2020][CO20])</sup>。

|

||||

|

||||

## 参考文献 {#references}

|

||||

|

||||

- Abdelwahab Yousef, A. J. (2017). Male Breast Cancer: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. *Seminars in Oncology*, *44*(4), 267–272. \[DOI:[10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.11.002][AY17]]

|

||||

- Anders, C. K., Johnson, R., Litton, J., Phillips, M., & Bleyer, A. (2009). Breast Cancer Before Age 40 Years. *Seminars in Oncology*, *36*(3), 237–249. \[DOI:[10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.001][A09]]

|

||||

- Asscheman, H., Gooren, L., & Eklund, P. (1989). Mortality and morbidity in transsexual patients with cross-gender hormone treatment. *Metabolism*, *38*(9), 869–873. \[DOI:[10.1016/0026-0495(89)90233-3][AGE89]]

|

||||

- Asscheman, H., Giltay, E. J., Megens, J. A., de Ronde, W., van Trotsenburg, M. A., & Gooren, L. J. (2011). A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. *European Journal of Endocrinology*, *164*(4), 635–642. \[DOI:[10.1530/eje-10-1038][A11]]

|

||||

- Ban, K. A., & Godellas, C. V. (2014). Epidemiology of Breast Cancer. *Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America*, *23*(3), 409–422. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.soc.2014.03.011][BG14]]

|

||||

- Benjamin, H. (1964). Clinical Aspects of Transsexualism in the Male and Female. *American Journal of Psychotherapy*, *18*(3), 458–469. \[DOI:[10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1964.18.3.458][B64]]

|

||||

- Benjamin, H. (1966). *The Transsexual Phenomenon*. New York: Julian Press. \[[Google 学术][B66-GS]] \[[Google 阅读][B66]] \[[PDF][B66-PDF]]

|

||||

- Benz, C. C. (2008). Impact of aging on the biology of breast cancer. *Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology*, *66*(1), 65–74. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.09.001][B08]]

|

||||

- Biro, F. M., & Wolff, M. S. (2011). Puberty as a Window of Susceptibility. In Russo, J. (Ed.). *Environment and Breast Cancer* (pp. 29–41). New York: Springer New York. \[DOI:[10.1007/978-1-4419-9896-5\_2][BW11]]

|

||||

- Biro, F. M., & Deardorff, J. (2013). Identifying Opportunities for Cancer Prevention During Preadolescence and Adolescence: Puberty as a Window of Susceptibility. *Journal of Adolescent Health*, *52*(5), S15–S20. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.019][BD13]]

|

||||

- Biro, F. M., Huang, B., Wasserman, H., Gordon, C. M., & Pinney, S. M. (2021). Pubertal Growth, IGF-1, and Windows of Susceptibility: Puberty and Future Breast Cancer Risk. *Journal of Adolescent Health*, *68*(3), 517–522. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.016][B20]]

|

||||

- Braun, H., Nash, R., Tangpricha, V., Brockman, J., Ward, K., & Goodman, M. (2017). Cancer in Transgender People: Evidence and Methodological Considerations. *Epidemiologic Reviews*, *39*(1), 93–107. \[DOI:[10.1093/epirev/mxw003][B17]]

|

||||

- Brisken, C., Hess, K., & Jeitziner, R. (2015). Progesterone and Overlooked Endocrine Pathways in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis. *Endocrinology*, *156*(10), 3442–3450. \[DOI:[10.1210/en.2015-1392][BHJ15]]

|

||||

- Brown, G. R., & Jones, K. T. (2014). Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. *Breast Cancer Research and Treatment*, *149*(1), 191–198. \[DOI:[10.1007/s10549-014-3213-2][BJ15]]

|

||||

- Brown, G. R., & Jones, K. T. (2014). Racial Health Disparities in a Cohort of 5,135 Transgender Veterans. *Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities*, *1*(4), 257–266. \[DOI:[10.1007/s40615-014-0032-4][BJ14]]

|

||||

- Brown, G. R. (2015). Breast Cancer in Transgender Veterans: A Ten-Case Series. *LGBT Health*, *2*(1), 77–80. \[DOI:[10.1089/lgbt.2014.0123][B15]]

|

||||

- Brown, G. R., & Jones, K. T. (2016). Mental Health and Medical Health Disparities in 5135 Transgender Veterans Receiving Healthcare in the Veterans Health Administration: A Case–Control Study. *LGBT Health*, *3*(2), 122–131. \[DOI:[10.1089/lgbt.2015.0058][BJ16]]

|

||||

- Cancer Research UK. (2020). *Breast cancer incidence (invasive) statistics.* Cancer Research UK. \[[URL][CRUK20]]

|

||||

- Cancer.Net. (2020). *Breast Cancer: Statistics.* American Society of Clinical Oncology. \[[URL][CANCER20-ALT]]

|

||||

- Chaligné, R., Popova, T., Mendoza-Parra, M., Saleem, M. M., Gentien, D., Ban, K., Piolot, T., Leroy, O., Mariani, O., Gronemeyer, H., Vincent-Salomon, A., Stern, M., & Heard, E. (2015). The inactive X chromosome is epigenetically unstable and transcriptionally labile in breast cancer. *Genome Research*, *25*(4), 488–503. \[DOI:[10.1101/gr.185926.114][C15]]

|

||||

- Chlebowski, R. T., Aragaki, A. K., & Anderson, G. L. (2015). Menopausal Hormone Therapy Influence on Breast Cancer Outcomes in the Women’s Health Initiative. *Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network*, *13*(7), 917–924. \[DOI:[10.6004/jnccn.2015.0106][CAA15]]

|

||||

- Chowdhry, D. N., & O’Connell, A. M. (2020). Breast Imaging in Transgender Patients. *Journal of Breast Imaging*, *2*(2), 161–167. \[DOI:[10.1093/jbi/wbz092][CO20]]

|

||||

- Cline, J. M. (2007). Assessing the mammary gland of nonhuman primates: effects of endogenous hormones and exogenous hormonal agents and growth factors. *Birth Defects Research Part B: Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology*, *80*(2), 126–146. \[DOI:[10.1002/bdrb.20112][C07]]

|

||||

- Coe, F. L., & Parks, J. H. (1989). The Risks of Oral Contraceptives and Estrogen Replacement Therapy. *Perspectives in Biology and Medicine*, *33*(1), 86–106. \[DOI:[10.1353/pbm.1990.0026][CP89]]

|

||||

- Coelingh Bennink, H. J., Verhoeven, C., Dutman, A. E., & Thijssen, J. (2017). The use of high-dose estrogens for the treatment of breast cancer. *Maturitas*, *95*, 11–23. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.10.010][CB17]]

|

||||

- Colditz, G. A. (2000). Cumulative Risk of Breast Cancer to Age 70 Years According to Risk Factor Status: Data from the Nurses’ Health Study. *American Journal of Epidemiology*, *152*(10), 950–964. \[DOI:[10.1093/aje/152.10.950][CR00]]

|

||||

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. (2019). Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. *The Lancet*, *394*(10204), 1159–1168. \[DOI:[10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31709-x][CGHF19]]

|

||||

- Davey, D. A. (2018). Menopausal hormone therapy: a better and safer future. *Climacteric*, *21*(5), 454–461. \[DOI:[10.1080/13697137.2018.1439915][D18]]

|

||||

- de Blok, C. J., Wiepjes, C. M., Nota, N. M., van Engelen, K., Adank, M. A., Dreijerink, K. M., Barbé, E., Konings, R. H., & den Heijer, M. (2018). Breast cancer in transgender persons receiving gender affirming hormone treatment: results of a nationwide cohort study. *Endocrine Abstracts*, *56* \[*20th European Congress of Endocrinology 2018, 19–22 May 2018, Barcelona, Spain*], 490–490 (abstract no. P955). \[DOI:[10.1530/endoabs.56.p955][DB18-DOI]] \[[PDF][DB18-PDF]]

|

||||

- de Blok, C. J., Dreijerink, K. M., & den Heijer, M. (2019). Cancer Risk in Transgender People. *Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America*, *48*(2), 441–452. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.ecl.2019.02.005][BDH19]]

|

||||

- de Blok, C. J., Wiepjes, C. M., Nota, N. M., van Engelen, K., Adank, M. A., Dreijerink, K. M., Barbé, E., Konings, I. R., & den Heijer, M. (2019). Breast cancer risk in transgender people receiving hormone treatment: nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. *BMJ*, *365*, l1652. \[DOI:[10.1136/bmj.l1652][DB19]]

|

||||

- Dente, E., Farneth, R., Purks, J., & Torelli, S. (2019). Evaluating risks, reported cases and screening recommendations for breast cancer in transgender patients. *Georgetown Medical Review*, *3*(1). \[DOI:[10.52504/001c.7774][D19-DOI]]

|

||||

- Di Oto, E., Monti, V., Cucchi, M. C., Masetti, R., Varga, Z., & Foschini, M. P. (2015). X chromosome gain in male breast cancer. *Human Pathology*, *46*(12), 1908–1912. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.humpath.2015.08.008][DO15]]

|

||||

- Di Oto, E., Biserni, G. B., Varga, Z., Morandi, L., Cucchi, M. C., Masetti, R., & Foschini, M. P. (2018). X chromosome gain is related to increased androgen receptor expression in male breast cancer. *Virchows Archiv*, *473*(2), 155–163. \[DOI:[10.1007/s00428-018-2377-2][DO18]]

|

||||

- Dix, D., & Cohen, P. (1982). The incidence of breast cancer: analysis of the age dependence. *Anticancer Research*, *2*(1-2), 23–7. \[[Google 学术][DC82-GS]] \[[PubMed][DC82]] \[[PDF][DC82-PDF]]

|

||||

- Dworin, M. (1961). The Rationale of Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer. *CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians*, *11*(2), 48–54. \[DOI:[10.3322/canjclin.11.2.48][D61]]

|

||||

- Feldman, J., Brown, G. R., Deutsch, M. B., Hembree, W., Meyer, W., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F., Tangpricha, V., T’Sjoen, G., & Safer, J. D. (2016). Priorities for transgender medical and healthcare research. *Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity*, *23*(2), 180–187. \[DOI:[10.1097/med.0000000000000231][F16]]

|

||||

- Ferzoco, R. M., & Ruddy, K. J. (2016). The Epidemiology of Male Breast Cancer. *Current Oncology Reports*, *18*, 1. \[DOI:[10.1007/s11912-015-0487-4][FR16]]

|

||||

- Forrest, A. P. (1989). Endocrine management of breast cancer. *Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B. Biological Sciences*, *95* \[*Oestrogen and the Human Breast*], 1–10. \[DOI:[10.1017/s0269727000010502][F89]]

|

||||

- Fournier, A., Berrino, F., & Clavel-Chapelon, F. (2007). Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. *Breast Cancer Research and Treatment*, *107*(1), 103–111. \[DOI:[10.1007/s10549-007-9523-x][F07]]

|

||||

- Gellhorn, A., & Jones, L. O. (1949). Chemotherapy of malignant disease. *The American Journal of Medicine*, *6*(2), 188–231. \[DOI:[10.1016/0002-9343(49)90017-0][GJ49]]

|

||||

- Giordano, S. H. (2005). A Review of the Diagnosis and Management of Male Breast Cancer. *The Oncologist*, *10*(7), 471–479. \[DOI:[10.1634/theoncologist.10-7-471][G05]]

|

||||

- Giordano, S. H. (2018). Breast Cancer in Men. *New England Journal of Medicine*, *378*(24), 2311–2320. \[DOI:[10.1056/nejmra1707939][G18]]

|

||||

- Gompel, A., Levy, D., Chaouat, M., Kazem, A., Hugol, D., Daraı̈, E., Decroix, Y., & Rostène, W. (2002). Is there a place for progestin agents in breast cancer prevention? *International Congress Series*, *1229*, 143–150. \[DOI:[10.1016/s0531-5131(01)00467-8][G02]]

|

||||

- Gooren, L. J. (2011). Care of Transsexual Persons. *New England Journal of Medicine*, *364*(13), 1251–1257. \[DOI:[10.1056/nejmcp1008161][G11]]

|

||||

- Gooren, L. J., van Trotsenburg, M. A., Giltay, E. J., & van Diest, P. J. (2013). Breast Cancer Development in Transsexual Subjects Receiving Cross-Sex Hormone Treatment. *The Journal of Sexual Medicine*, *10*(12), 3129–3134. \[DOI:[10.1111/jsm.12319][G13]]

|

||||

- Göretzlehner, G., Ackermann, W., Angelow, K., Bergmann, G., Bieck, E., Golbs, S., & Kliem, O. (2002). Pharmakokinetik von Estron, Estradiol, FSH, LH und Prolaktin nach intramuskulärer Applikation von 5 mg Estradiolvalerat. \[Pharmacokinetics of estradiol valerate in postmenopausal women after intramuscular administration.] *Journal für Menopause*, *9*(2), 46–49. \[[Google 学术][GORE02-GS]] \[[URL][GORE02]] \[[PDF][GORE02-PDF]] \[[英译本][GORE02-ENG]]

|

||||

- Green, R. B., Sethi, R. S., & Lindner, H. H. (1964). Treatment of advanced carcinoma of the breast. *The American Journal of Surgery*, *108*(1), 107–121. \[DOI:[10.1016/0002-9610(64)90094-7][GSL64]]

|

||||

- Herrmann, J. B. (1947). Effect of estrogenic hormone on advanced carcinoma of the female breast. *Archives of Surgery*, *54*(1), 1–9. \[DOI:[10.1001/archsurg.1947.01230070004001][HAW47]]

|

||||

- Hilakivi-Clarke, L., de Assis, S., Warri, A., & Luoto, R. (2012). Pregnancy hormonal environment and mother’s breast cancer risk. *Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation*, *9*(1), 11–23. \[DOI:[10.1515/hmbci-2012-0019][HC12]]

|

||||

- Hughes, I. A. (2010). Evaluation and Management of Disorders of Sex Development. In Brook, C. G. D., Clayton, P. E., & Brown, R. S. (Eds.). *Brook’s Clinical Pediatric Endocrinology, 6th Edition* (pp. 192–212). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. \[DOI:[10.1002/9781444316728.ch9][H09]]

|

||||

- Hughes, I. A., Davies, J. D., Bunch, T. I., Pasterski, V., Mastroyannopoulou, K., & MacDougall, J. (2012). Androgen insensitivity syndrome. *The Lancet*, *380*(9851), 1419–1428. \[DOI:[10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60071-3][H12]]

|

||||

- Hulka, B. S., Chambless, L. E., Deubner, D. C., & Wilkinson, W. E. (1982). Breast cancer and estrogen replacement therapy. *American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology*, *143*(6), 638–644. \[DOI:[10.1016/0002-9378(82)90108-9][H82]]

|

||||

- Husby, A., Wohlfahrt, J., Øyen, N., & Melbye, M. (2018). Pregnancy duration and breast cancer risk. *Nature Communications*, *9*(1), 4255. \[DOI:[10.1038/s41467-018-06748-3][H18]]

|

||||

- Ji, L., Jing, C., Zhuang, S., Pan, W., & Hu, X. (2019). Effect of age at first use of oral contraceptives on breast cancer risk. *Medicine*, *98*(36), e15719–e15719. \[DOI:[10.1097/md.0000000000015719][J19]]

|

||||

- Kahlenborn, C., Modugno, F., Potter, D. M., & Severs, W. B. (2006). Oral Contraceptive Use as a Risk Factor for Premenopausal Breast Cancer: A Meta-analysis. *Mayo Clinic Proceedings*, *81*(10), 1290–1302. \[DOI:[10.4065/81.10.1290][KAHL06]]

|

||||

- Karlsson, C. T., Malmer, B., Wiklund, F., & Grönberg, H. (2006). Breast Cancer as a Second Primary in Patients With Prostate Cancer—Estrogen Treatment or Association With Family History of Cancer? *Journal of Urology*, *176*(2), 538–543. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.036][K06]]

|

||||

- Kennedy, B.J. (1956). Effects of steroids in women with breast cancer. In Engle, E. T., & Pincus, G. (Eds.). *Hormones and the Aging Process: Proceedings of a Conference Held at Arden House, Harriman, New York, 1955* (pp. 253–272). New York: Academic Press. \[[Google 学术][K56-GS]] \[[Google 阅读][K56]]

|

||||

- Kennedy, B. J. (1957). The Present Status of Hormone Therapy in Advanced Breast Cancer. *Radiology*, *69*(3), 330–340. \[DOI:[10.1148/69.3.330][K57]]

|

||||

- Kennedy, B. J. (1962). Massive estrogen administration in premenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer. *Cancer*, *15*(3), 641–648. \[DOI:[10.1002/1097-0142(196205/06)15:3<641::aid-cncr2820150330>3.0.co;2-9][K62]]

|

||||

- Kennedy, B. J. (1964). Estrogenic Hormone Therapy in Advanced Breast Cancer.. *Annals of Internal Medicine*, *60*(4), 718–718. \[DOI:[10.7326/0003-4819-60-4-718\_1][K64]]

|

||||

- Kuhl, H. (2005). Breast cancer risk in the WHI study: The problem of obesity. *Maturitas*, *51*(1), 83–97. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.02.018][K05]]

|

||||

- Kuhl, H., & Schneider, H. P. (2013). Progesterone – promoter or inhibitor of breast cancer. *Climacteric*, *16*(Suppl 1), 54–68. \[DOI:[10.3109/13697137.2013.768806][K13]]

|

||||

- Lin, I., Chen, D., Chang, Y., Lee, Y., Su, C., Cheng, C., Tsai, Y., Ng, S., Chen, H., Lee, M., Chen, H., Suen, S., Chen, Y., Liu, T., Chang, C., & Hsu, M. (2015). Hierarchical Clustering of Breast Cancer Methylomes Revealed Differentially Methylated and Expressed Breast Cancer Genes. *PLOS ONE*, *10*(2), e0118453. \[DOI:[10.1371/journal.pone.0118453][L15]]

|

||||

- Lumachi, F. (2015). Current medical treatment of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. *World Journal of Biological Chemistry*, *6*(3), 231–239. \[DOI:[10.4331/wjbc.v6.i3.231][LSB15]]

|

||||

- Mauvais-Jarvis, P., Kuttenn, F., & Gompel, A. (1986). Antiestrogen action of progesterone in breast tissue. *Breast Cancer Research and Treatment*, *8*(3), 179–188. \[DOI:[10.1007/bf01807330][MKG86]]

|

||||

- Mirkin, S. (2018). Evidence on the use of progesterone in menopausal hormone therapy. *Climacteric*, *21*(4), 346–354. \[DOI:[10.1080/13697137.2018.1455657][M18]]

|

||||

- Mocellin, S., Goodwin, A., & Pasquali, S. (2019). Risk-reducing medications for primary breast cancer: a network meta-analysis. *Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews*, *2019*(4), CD012191. \[DOI:[10.1002/14651858.cd012191.pub2][MGP19]]

|

||||

- Momenimovahed, Z., & Salehiniya, H. (2019). Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. *Breast Cancer: Targets and Therapy*, *11*, 151–164. \[DOI:[10.2147/bctt.s176070][MS18]]

|

||||

- Mueck, A. O., & Ruan, X. (2011). Benefits and risks during HRT: main safety issue breast cancer. *Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation*, *5*(2), 105–116. \[DOI:[10.1515/hmbci.2011.014][MR11]]

|

||||

- Mueller, A., & Gooren, L. (2008). Hormone-related tumors in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. *European Journal of Endocrinology*, *159*(3), 197–202. \[DOI:[10.1530/eje-08-0289][MG08]]

|

||||

- Nakopoulou, L., Panayotopoulou, E. G., Giannopoulou, I., Tsirmpa, I., Katsarou, S., Mylona, E., Alexandrou, P., & Keramopoulos, A. (2006). Extra copies of chromosomes 16 and X in invasive breast carcinomas are related to aggressive phenotype and poor prognosis. *Journal of Clinical Pathology*, *60*(7), 808–815. \[DOI:[10.1136/jcp.2006.037838][M06]]

|

||||

- Nathanson, I. T. (1947). Hormonal Alteration of Advanced Cancer of the Breast. *Surgical Clinics of North America*, *27*(5), 1144–1150. \[DOI:[10.1016/s0039-6109(16)32241-1][N47]]

|

||||

- Nathanson, I. T. (1951). Sex Hormones and Castration in Advanced Breast Cancer. *Radiology*, *56*(4), 535–552. \[DOI:[10.1148/56.4.535][N51]]

|

||||

- Nelson, H. D., Fu, R., Zakher, B., Pappas, M., & McDonagh, M. (2019). Medication Use for the Risk Reduction of Primary Breast Cancer in Women. *JAMA*, *322*(9), 868–886. \[DOI:[10.1001/jama.2019.5780][N19]]

|

||||

- Nichols, H. B., Schoemaker, M. J., Cai, J., Xu, J., Wright, L. B., Brook, M. N., Jones, M. E., Adami, H., Baglietto, L., Bertrand, K. A., Blot, W. J., Boutron-Ruault, M., Dorronsoro, M., Dossus, L., Eliassen, A. H., Giles, G. G., Gram, I. T., Hankinson, S. E., Hoffman-Bolton, J., Kaaks, R., Key, T. J., Kitahara, C. M., Larsson, S. C., Linet, M., Merritt, M. A., Milne, R. L., Pala, V., Palmer, J. R., Peeters, P. H., Riboli, E., Sund, M., Tamimi, R. M., Tjønneland, A., Trichopoulou, A., Ursin, G., Vatten, L., Visvanathan, K., Weiderpass, E., Wolk, A., Zheng, W., Weinberg, C. R., Swerdlow, A. J., & Sandler, D. P. (2018). Breast Cancer Risk After Recent Childbirth. *Annals of Internal Medicine*, *170*(1), 22–31. \[DOI:[10.7326/m18-1323][N19]]

|

||||

- Ottini, L., & Capalbo, C. (2017). Male Breast Cancer. In Veronesi, U., Goldhirsch, A., Veronesi, P., Gentilini, O. D., & Leonardi, M. C. (Eds.). *Breast Cancer: Innovations in Research and Management* (pp. 753–762). Cham: Springer. \[DOI:[10.1007/978-3-319-48848-6\_63][OC17]]

|

||||

- Palmieri, C., Patten, D. K., Januszewski, A., Zucchini, G., & Howell, S. J. (2014). Breast cancer: Current and future endocrine therapies. *Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology*, *382*(1), 695–723. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.001][P14]]

|

||||

- Pearson, O. H. (1954). Evaluation of endocrine therapy for advanced breast cancer. *JAMA*, *154*(3), 234–239. \[DOI:[10.1001/jama.1954.02940370046013][P54]]

|

||||

- Pearson, O. H., & Lipsett, M. B. (1956). Endocrine Management of Metastatic Breast Cancer. *Medical Clinics of North America*, *40*(3), 761–772. \[DOI:[10.1016/s0025-7125(16)34564-3][PL56]]

|

||||

- Prentice, R. L. (2008). Women’s Health Initiative Studies of Postmenopausal Breast Cancer. In Li, J. J., Li, S. A., Mohla, S., Rochefort, H., & Maudelonde, T. (Eds.). *Hormonal Carcinogenesis V* (*Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Volume 617*) (pp. 151–160). New York: Springer New York. \[DOI:[10.1007/978-0-387-69080-3\_14][P08]]

|

||||

- Rajkumar, L., Guzman, R. C., Yang, J., Thordarson, G., Talamantes, F., & Nandi, S. (2003). Prevention of mammary carcinogenesis by short-term estrogen and progestin treatments. *Breast Cancer Research*, *6*(1), R31. \[DOI:[10.1186/bcr734][R03]]

|

||||

- *Reactions Weekly.* (2019). Hormones increase breast cancer risk in Dutch transgender women. *Reactions Weekly*, *1754*, 9–9. \[DOI:[10.1007/s40278-019-62242-2][RW19]]

|

||||

- Sasco, A. J., Lowenfels, A. B., & Jong, P. P. (1993). Review article: Epidemiology of male breast cancer. A meta-analysis of published case-control studies and discussion of selected aetiological factors. *International Journal of Cancer*, *53*(4), 538–549. \[DOI:[10.1002/ijc.2910530403][SLP93]]

|

||||

- Satram, S. (2006). *Genetic and environmental factors and male breast cancer risk*. (Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Irvine.) \[[Google 学术][S06-GS]] \[[URL][S06-ALT]]

|

||||

- Silverberg, M. J., Nash, R., Becerra-Culqui, T. A., Cromwell, L., Getahun, D., Hunkeler, E., Lash, T. L., Millman, A., Quinn, V. P., Robinson, B., Roblin, D., Slovis, J., Tangpricha, V., & Goodman, M. (2017). Cohort study of cancer risk among insured transgender people. *Annals of Epidemiology*, *27*(8), 499–501. \[DOI:[10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.07.007][S17]]

|

||||

- Stoll, B. A. (1973). Hypothesis: Breast Cancer Regression under Oestrogen Therapy. *BMJ*, *3*(5877), 446–450. \[DOI:[10.1136/bmj.3.5877.446][S73]]

|

||||

- Stute, P., Wildt, L., & Neulen, J. (2018). The impact of micronized progesterone on breast cancer risk: a systematic review. *Climacteric*, *21*(2), 111–122. \[DOI:[10.1080/13697137.2017.1421925][SWN18]]

|

||||

- Sun, Y., Zhao, Z., Yang, Z., Xu, F., Lu, H., Zhu, Z., Shi, W., Jiang, J., Yao, P., & Zhu, H. (2017). Risk Factors and Preventions of Breast Cancer. *International Journal of Biological Sciences*, *13*(11), 1387–1397. \[DOI:[10.7150/ijbs.21635][S17]]

|

||||

- Sutherland, N., Espinel, W., Grotzke, M., & Colonna, S. (2020). Unanswered Questions: Hereditary breast and gynecological cancer risk assessment in transgender adolescents and young adults. *Journal of Genetic Counseling*, *29*(4), 625–633. \[DOI:[10.1002/jgc4.1278][S20]]

|

||||

- T’Sjoen, G., Arcelus, J., Gooren, L., Klink, D. T., & Tangpricha, V. (2018). Endocrinology of Transgender Medicine. *Endocrine Reviews*, *40*(1), 97–117. \[DOI:[10.1210/er.2018-00011][TS19]]

|

||||

- Thellenberg, C., Malmer, B., Tavelin, B., & Grönberg, H. (2003). Second Primary Cancers in Men With Prostate Cancer: An Increased Risk of Male Breast Cancer. *Journal of Urology*, *169*(4), 1345–1348. \[DOI:[10.1097/01.ju.0000056706.88960.7c][T03]]

|

||||

- Tiefenbacher, K., & Daxenbichler, G. (2008). The Role of Androgens in Normal and Malignant Breast Tissue. *Breast Care*, *3*(5), 325–331. \[DOI:[10.1159/000158055][TD08]]

|

||||

- Van Kesteren, P. J., Asscheman, H., Megens, J. A., & Gooren, L. J. (1997). Mortality and morbidity in transsexual subjects treated with cross-sex hormones. *Clinical Endocrinology*, *47*(3), 337–343. \[DOI:[10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2601068.x][VK97]]

|

||||

- Wierckx, K., Mueller, S., Weyers, S., Van Caenegem, E., Roef, G., Heylens, G., & T’Sjoen, G. (2012). Long‐Term Evaluation of Cross‐Sex Hormone Treatment in Transsexual Persons. *The Journal of Sexual Medicine*, *9*(10), 2641–2651. \[DOI:[10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02876.x][W12]]

|

||||

- Wren, B. G., & Eden, J. A. (1996). Do Progestogens Reduce The Risk of Breast Cancer? A Review of the Evidence. *Menopause*, *3*(1), 4–12. \[DOI:[10.1097/00042192-199603010-00003][WE96]]

|

||||

- Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. (2002). Risks and Benefits of Estrogen Plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal Women: Principal Results From the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. *JAMA*, *288*(3), 321–333. \[DOI:[10.1001/jama.288.3.321][WHI02]]

|

||||

- Zhu, H., Lei, X., Feng, J., & Wang, Y. (2012). Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. *The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care*, *17*(6), 402–414. \[DOI:[10.3109/13625187.2012.715357][Z12]]

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

## 译文修订历史 {#revise-history}

|

||||

## 译文修订记录 {#revision}

|

||||

|

||||

```csv

|

||||

时间,备注

|

||||

2022 年 8 月 28 日,首次翻译。

|

||||

2022 年 11 月 28 日,移除一条已删除的原文链接。

|

||||

2023 年 3 月 29 日,第一次修订:\n增补“摘要”与“参考文献”;\n更正孕酮(progesterone)等多处叙述;\n补齐链接。

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

[bg14]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2014.03.011

|

||||

[y17]: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.11.002

|

||||

[oc17]: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48848-6_63

|

||||

[ms18]: https://doi.org/10.2147/BCTT.S176070

|

||||

[dc82]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7114800/

|

||||

[a09]: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.001

|

||||

[b08]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.09.001

|

||||

[cr00]: https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/152.10.950

|

||||

[bhj15]: https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2015-1392

|

||||

[cruk]: https://perma.cc/GE2T-B68E

|

||||

[s06]: https://search.proquest.com/docview/305372484

|

||||

[fr16]: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-015-0487-4

|

||||

[g18]: http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1707939

|

||||

[mgp19]: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012191.pub2

|

||||

[n19]: http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.5780

|

||||

[c07]: https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrb.20112

|

||||

[lsb15]: https://doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v6.i3.231

|

||||

[p14]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.001

|

||||

[haw47]: http://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1947.01230070004001

|

||||

[n47]: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6109(16)32241-1

|

||||

[gj49]: https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(49)90017-0

|

||||

[n51]: https://doi.org/10.1148/56.4.535

|

||||

[p54]: http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1954.02940370046013

|

||||

[pl56]: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-7125(16)34564-3

|

||||

[k56]: https://books.google.com/books?id=BC3gBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA253

|

||||

[k57]: https://doi.org/10.1148/69.3.330

|

||||

[d61]: https://doi.org/10.3322/canjclin.11.2.48

|

||||

[k62]: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(196205/06)15:3%3C641::AID-CNCR2820150330%3E3.0.CO;2-9

|

||||

[gsl64]: https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(64)90094-7

|

||||

[k64]: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-60-4-718_1

|

||||

[s73]: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.3.5877.446

|

||||

[f89]: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269727000010502

|

||||

[cghf19]: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31709-X

|

||||

[cghf19-table]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Worldwide_epidemiological_evidence_on_breast_cancer_risk_with_menopausal_hormone_therapy

|

||||

[mkg86]: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01807330

|

||||

[we96]: http://doi.org/10.1097/00042192-199603010-00003

|

||||

[g02]: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0531-5131(01)00467-8

|

||||

[whi]: https://www.whi.org/

|

||||

[whi02]: http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.3.321

|

||||

[caa15]: https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2015.0106

|

||||

[nhs]: https://nurseshealthstudy.org

|

||||

[swn18]: https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1421925

|

||||

[m18]: https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2018.1455657

|

||||

[f07]: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-007-9523-x

|

||||

[ks13]: https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2013.768806

|

||||

[d18]: https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2018.1439915

|

||||

[wiki-1]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmacokinetics_of_progesterone#Oral_administration

|

||||

[graph-1]: https://web.archive.org/web/20220222215313/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Hormone_levels_with_oral_progesterone

|

||||

[cghf19-table2]: https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S014067361931709X-mmc1.pdf#page=29

|

||||

[k05]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.02.018

|

||||

[p08]: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-69080-3_14

|

||||

[mr11]: https://doi.org/10.1515/HMBCI.2011.014

|

||||

[nich19]: https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-1323

|

||||

[h18]: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06748-3

|

||||

[graph-2]: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Estrogen_and_progesterone_levels_during_pregnancy_in_women.png

|

||||

[r03]: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr734

|

||||

[b17]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.10.010

|

||||

[slp93]: https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2910530403

|

||||

[g05]: https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.10-7-471

|

||||

[t03]: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000056706.88960.7c

|

||||

[k06]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.036

|

||||

[app-1]: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1oqPdRM6gON2hwl6QO1e0GdseYoK5X0J5AtxDZ5hB5tk/view

|

||||

[age89]: https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(89)90233-3

|

||||

[k97]: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2601068.x

|

||||

[mg08]: https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-08-0289

|

||||

[a11]: https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-10-1038

|

||||

[g13]: https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12319

|

||||

[b18]: https://web.archive.org/web/20201112033637/https://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0056/ea0056p955.htm

|

||||

[b19]: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1652

|

||||

[f16]: http://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000231

|

||||

[table1]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Worldwide_epidemiological_evidence_on_breast_cancer_risk_with_menopausal_hormone_therapy

|

||||

[graph1]: https://web.archive.org/web/20220222215313/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Hormone_levels_with_oral_progesterone

|

||||

[table2]: https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S014067361931709X-mmc1.pdf#page=29

|

||||

[graph2]: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Estrogen_and_progesterone_levels_during_pregnancy_in_women.png

|

||||

|

||||

[wiki1]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breast_development

|

||||

[wiki2]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breast_cancer

|

||||

[wiki3]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menopause

|

||||

[wiki3-p]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menopause#Postmenopause

|

||||

[wiki4]: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5122(99)00075-4

|

||||

[wiki5]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surveillance,_Epidemiology,_and_End_Results

|

||||

[wiki6]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Cancer_Institute

|

||||

[wiki7]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menarche

|

||||

[wiki8]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiestrogen

|

||||

[wiki9]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selective_estrogen_receptor_modulator

|

||||

[wiki10]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tamoxifen

|

||||

[wiki11]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aromatase_inhibitor

|

||||

[wiki12]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anastrozole

|

||||

[wiki13]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemoprophylaxis

|

||||

[wiki14]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiprogestogen

|

||||

[wiki15]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Onapristone

|

||||

[wiki16]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mifepristone

|

||||

[wiki17]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hormone_replacement_therapy

|

||||

[wiki18]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_Health_Initiative

|

||||

[wiki19]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conjugated_estrogens

|

||||

[wiki20]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medroxyprogesterone_acetate

|

||||

[wiki21]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nurses%27_Health_Study

|

||||

[wiki22]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poisson_regression

|

||||

[wiki23]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bioidentical_hormone_replacement_therapy

|

||||

[wiki24-oa]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmacokinetics_of_progesterone#Oral_administration

|

||||

[wiki25]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timing_hypothesis_(menopausal_hormone_therapy)

|

||||

[wiki26]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VU_University_Medical_Center

|

||||

[wiki27]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veterans_Health_Administration

|

||||

[wiki28]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaiser_Permanente

|

||||

[wiki29]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Benjamin

|

||||

[wiki30]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combined_hormonal_contraception

|

||||

[wiki31]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sex_chromosome

|

||||

[wiki32]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X_chromosome

|

||||

[wiki33]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y_chromosome

|

||||

[wiki34]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karyotype

|

||||

[wiki35]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aneuploidy

|

||||

[wiki36]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X-inactivation

|

||||

[wiki37]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klinefelter_syndrome

|

||||

[wiki38]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complete_androgen_insensitivity_syndrome

|

||||

|

||||

[BG14]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2014.03.011

|

||||

[AY17]: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.11.002

|

||||

[OC17]: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48848-6_63

|

||||

[MS18]: https://doi.org/10.2147/BCTT.S176070

|

||||

[DC82]: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7114800/

|

||||

[A09]: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.001

|

||||

[B08]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.09.001

|

||||

[CR00]: https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/152.10.950

|

||||

[BHJ15]: https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2015-1392

|

||||

[CRUK20]: https://web.archive.org/web/20200804203755/https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer/incidence-invasive

|

||||

[S06]: https://search.proquest.com/docview/305372484

|

||||

[FR16]: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-015-0487-4

|

||||

[G18]: http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1707939

|

||||

[MGP19]: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012191.pub2

|

||||

[N19]: http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.5780

|

||||

[C07]: https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrb.20112

|

||||

[LSB15]: https://doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v6.i3.231

|

||||

[P14]: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.001

|

||||

[HAW47]: http://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1947.01230070004001

|

||||

[N47]: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6109(16)32241-1

|

||||

[GJ49]: https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(49)90017-0

|

||||

[N51]: https://doi.org/10.1148/56.4.535

|

||||

[P54]: http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1954.02940370046013

|

||||

[PL56]: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-7125(16)34564-3

|

||||

[K56]: https://books.google.com/books?id=BC3gBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA253

|

||||

[K57]: https://doi.org/10.1148/69.3.330

|

||||

[D61]: https://doi.org/10.3322/canjclin.11.2.48

|

||||

[K62]: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(196205/06)15:3%3C641::AID-CNCR2820150330%3E3.0.CO;2-9

|

||||

[GSL64]: https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(64)90094-7

|

||||

[K64]: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-60-4-718_1

|

||||

[S73]: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.3.5877.446

|

||||